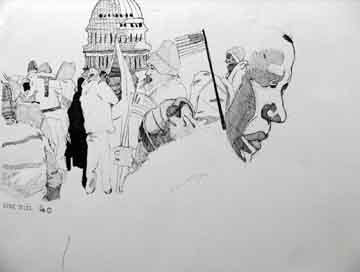

Senior Scott Yu shares his perspectives on American liberty and freedom since the time of the Pilgrims in the following persuasive essay. Scott Yu won a 2010 Creativity & Citizenship Medal for this piece, Finishing the Journey.

The year is 1620. Under a pallid November sky, dark cerulean waves gently lap against cold sand. Atop dunes, shrubby pines overlook the bare, weathered shore. The day moves slowly, reluctant to expose the sweet wood further inland to the bitter winds of the coming winter. At first glance, it is a typical autumn day: small fish swim about in the chilly waters while the vegetation on shore, swaying with the breeze, seems to cheer on the courageous creatures as they brave the cool waters… But today is far from typical. Beyond a low shoal appear square-rigged sails, and a ship of moderate size interrupts the horizon. As the ship approaches, a face appears, disappears, and then returns with many others. The travelers aboard the ship look like they have been at sea for too long. They are travel-worn, fatigued, and undernourished, yet, even from afar, a strange excitement can be seen, a peculiar enthusiasm radiating from faces that have become accustomed to seeing nothing but ocean. But theirs is something greater, for their eyes behold not only the shoreline of a new home but a harbor for religious freedom. They are the Pilgrims from Southampton, pioneers of religious freedom, and the founders of our country.

Nearly four centuries later, the journey of the Pilgrims’ has long ended, but their torch of religious freedom still lights the path of a longer journey ahead. In today’s post-modern era, scientific innovation is commonplace; democratization and globalization have spread to some of the remotest corners of the world; and freedoms and individual rights hold a solid place on the international agenda. But work still remains to be done. As a fundamental expression of autonomy and free will, international religious freedom should be a matter of consequence to every young American. Ensuring this freedom ought to be a central focus of United States policy because the U.S. government may only claim legitimacy at home and abroad if it enforces existing law; because intolerance in America’s own past demands that we provide for a freer future; and because religious freedom is a central component of our country’s origins and of the philosophy underlying the whole of our government.

In order for the United States government to claim rightful legitimacy to its own peoples as well as other countries on the global stage, it must demonstrate a respect and adherence to existing law. With the passing of the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) of 1998, the U.S. officially declared religious freedom as one of its overarching policy objectives. Furthermore, the U.S. has already acknowledged that “The right to freedom of religion is under renewed and, in some cases, increasing assault in many countries around the world. More than one‑half of the world’s population lives under regimes that severely restrict or prohibit the freedom of their citizens” (22 USC 6401, 1998). In addition, a recent annual report by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) named thirteen countries, including world powers such as China, as “egregious” violators of religious freedom and recommended that these be named “countries of particular concern” (CPC) for their systematic violations of religious liberty (USCIRF Annual Report 2009). These alarm bells call for action by the U.S. Secretary of State as well as by the President himself. In particular, CPC status requires the Secretary of State to pursue “a range of specific policy options to address serious violations of religious freedom” (USCIRF Annual Report 2009), and the U.S. One Hundred Fifth Congress has declared that “The entry into force of a binding agreement for the cessation of the violations shall be a primary objective for the President in responding to a foreign government that has engaged in or tolerated particularly severe violations of religious freedom” (Cong. Rec.). For the U.S. government to disregard its own exhortations and reports would surely weaken its legitimacy; hence, international religious freedom must be maintained as a policy objective.

Not only do the U.S.’s own legal actions mandate a policy focus on international religious freedom, but international law also commands a U.S. initiative in religious freedom endeavors. Presented and co-authored by the U.S.’s own First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) expresses adamantly and unambiguously in Article 18 that “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.” As one of the few countries with a permanent seat on the United Nations’ Security Council, the U.S. has an obligation as a global leader to guide the promotion of the UDHR, so that, one day, its promises can truly be “universal.” With partner countries on the Security Council having been labeled as countries showing marked disregard for religious freedom (People’s Republic of China and Russian Federation) (USCIRF Annual Report 2009), that the U.S. should set a positive, proactive example is even more imperative. Indeed, the fulfillment of this duty is essential for the U.S.’s image as a crusader for freedom and as a government determined to fulfill its own lofty promises; in a way, the U.S. is even committed to act by its status as a ratifying member of the multilateral treaty the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (United Nations MTDSG).

Though the alphabet soup of international laws such as the UDHR, ICCPR, IRFA, etc. are a modern phenomenon, throughout our history we have fought our own battles against intolerance. Considerable progress has been made: America has evolved from a loose association of towns populated by Christian whites to a vast land of religious diversity. Discrimination against religious minorities has decreased dramatically, and the last millennium has witnessed the rise of leaders of myriad faiths, including the first Roman Catholic President in 1961. Nonetheless, vestiges of intolerance still stain the new, progressive face of our country. A California political ad aired as recently as 2008 viciously targeted Mormons and roused public assault against Mormon establishments (Goldberg); and former President George H.W. Bush has stated in a public press conference, “No, I don’t know that Atheists should be considered as citizens, nor should they be considered patriots. This is one nation under God” (Dawkins, 43). These incidents, among countless others, show that the U.S. has not yet erased its past of intolerance and that increased efforts are needed to secure that future of freedom so passionately envisioned by our Founding Fathers.

When the Founders established our government centuries ago, they borrowed heavily from a philosophy of natural rights by the Englishman John Locke. Locke argued for the existence of certain unalienable rights – life, liberty, and property, which all men “hath by nature a power… to preserve… against the injuries and attempts of other men” (Locke). The importance of these principles to our government is evident in the Declaration of Independence, a document centered on Locke’s ideas. When the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Colony in 1620, they brought with them that same spirit of self-determination, which surfaces today as laws such as the IRFA and the UDHR.

It is crucial that, as young Americans, we be familiar with the continuity of America’s passion for individual liberties, for the task of finishing the journey toward international religious freedom – through community advocacy, smart voting, and individual open-mindedness – is in our hands.

Works Cited

Cong. Rec. 27 Jan. 1998: 1-30. U.S. Department of State. Web. 27 Nov. 2009. <http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/2297.pdf>.

Dawkins, Richard. The God Delusion. 2006. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006. Google Book Search. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Goldberg, Jonah. “An ugly attack on Mormons.” Editorial. The Los Angeles Times – California, L.A., Entertainment, and World news. The Los Angeles Times, 2009. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

International Religious Freedom Act of 1998. 22 USC. Sec. 6401. United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Locke, John. Two Treatises on Government. London: C. Baldwin, 1824. Center for History and News Media. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Smith, John. A Description of New England. Ed. Paul Royster. 1616. Lincoln: University of Nebraska – Lincoln, 2006. Digital Commons at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln. Web. 27 Nov. 2009. For descriptive material in introduction.

United States. United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. Annual Report 2009. Washington: n.p., 2009. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

The year is 1620. Under a pallid November sky, dark cerulean waves gently lap against cold sand. Atop dunes, shrubby pines overlook the bare, weathered shore. The day moves slowly, reluctant to expose the sweet wood further inland to the bitter winds of the coming winter. At first glance, it is a typical autumn day: small fish swim about in the chilly waters while the vegetation on shore, swaying with the breeze, seems to cheer on the courageous creatures as they brave the cool waters… But today is far from typical. Beyond a low shoal appear square-rigged sails, and a ship of moderate size interrupts the horizon. As the ship approaches, a face appears, disappears, and then returns with many others. The travelers aboard the ship look like they have been at sea for too long. They are travel-worn, fatigued, and undernourished, yet, even from afar, a strange excitement can be seen, a peculiar enthusiasm radiating from faces that have become accustomed to seeing nothing but ocean. But theirs is something greater, for their eyes behold not only the shoreline of a new home but a harbor for religious freedom. They are the Pilgrims from Southampton, pioneers of religious freedom, and the founders of our country.

Nearly four centuries later, the journey of the Pilgrims’ has long ended, but their torch of religious freedom still lights the path of a longer journey ahead. In today’s post-modern era, scientific innovation is commonplace; democratization and globalization have spread to some of the remotest corners of the world; and freedoms and individual rights hold a solid place on the international agenda. But work still remains to be done. As a fundamental expression of autonomy and free will, international religious freedom should be a matter of consequence to every young American. Ensuring this freedom ought to be a central focus of United States policy because the U.S. government may only claim legitimacy at home and abroad if it enforces existing law; because intolerance in America’s own past demands that we provide for a freer future; and because religious freedom is a central component of our country’s origins and of the philosophy underlying the whole of our government.

In order for the United States government to claim rightful legitimacy to its own peoples as well as other countries on the global stage, it must demonstrate a respect and adherence to existing law. With the passing of the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) of 1998, the U.S. officially declared religious freedom as one of its overarching policy objectives. Furthermore, the U.S. has already acknowledged that “The right to freedom of religion is under renewed and, in some cases, increasing assault in many countries around the world. More than one‑half of the world’s population lives under regimes that severely restrict or prohibit the freedom of their citizens” (22 USC 6401, 1998). In addition, a recent annual report by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) named thirteen countries, including world powers such as China, as “egregious” violators of religious freedom and recommended that these be named “countries of particular concern” (CPC) for their systematic violations of religious liberty (USCIRF Annual Report 2009). These alarm bells call for action by the U.S. Secretary of State as well as by the President himself. In particular, CPC status requires the Secretary of State to pursue “a range of specific policy options to address serious violations of religious freedom” (USCIRF Annual Report 2009), and the U.S. One Hundred Fifth Congress has declared that “The entry into force of a binding agreement for the cessation of the violations shall be a primary objective for the President in responding to a foreign government that has engaged in or tolerated particularly severe violations of religious freedom” (Cong. Rec.). For the U.S. government to disregard its own exhortations and reports would surely weaken its legitimacy; hence, international religious freedom must be maintained as a policy objective.

Not only do the U.S.’s own legal actions mandate a policy focus on international religious freedom, but international law also commands a U.S. initiative in religious freedom endeavors. Presented and co-authored by the U.S.’s own First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) expresses adamantly and unambiguously in Article 18 that “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.” As one of the few countries with a permanent seat on the United Nations’ Security Council, the U.S. has an obligation as a global leader to guide the promotion of the UDHR, so that, one day, its promises can truly be “universal.” With partner countries on the Security Council having been labeled as countries showing marked disregard for religious freedom (People’s Republic of China and Russian Federation) (USCIRF Annual Report 2009), that the U.S. should set a positive, proactive example is even more imperative. Indeed, the fulfillment of this duty is essential for the U.S.’s image as a crusader for freedom and as a government determined to fulfill its own lofty promises; in a way, the U.S. is even committed to act by its status as a ratifying member of the multilateral treaty the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (United Nations MTDSG).

Though the alphabet soup of international laws such as the UDHR, ICCPR, IRFA, etc. are a modern phenomenon, throughout our history we have fought our own battles against intolerance. Considerable progress has been made: America has evolved from a loose association of towns populated by Christian whites to a vast land of religious diversity. Discrimination against religious minorities has decreased dramatically, and the last millennium has witnessed the rise of leaders of myriad faiths, including the first Roman Catholic President in 1961. Nonetheless, vestiges of intolerance still stain the new, progressive face of our country. A California political ad aired as recently as 2008 viciously targeted Mormons and roused public assault against Mormon establishments (Goldberg); and former President George H.W. Bush has stated in a public press conference, “No, I don’t know that Atheists should be considered as citizens, nor should they be considered patriots. This is one nation under God” (Dawkins, 43). These incidents, among countless others, show that the U.S. has not yet erased its past of intolerance and that increased efforts are needed to secure that future of freedom so passionately envisioned by our Founding Fathers.

When the Founders established our government centuries ago, they borrowed heavily from a philosophy of natural rights by the Englishman John Locke. Locke argued for the existence of certain unalienable rights – life, liberty, and property, which all men “hath by nature a power… to preserve… against the injuries and attempts of other men” (Locke). The importance of these principles to our government is evident in the Declaration of Independence, a document centered on Locke’s ideas. When the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Colony in 1620, they brought with them that same spirit of self-determination, which surfaces today as laws such as the IRFA and the UDHR.

It is crucial that, as young Americans, we be familiar with the continuity of America’s passion for individual liberties, for the task of finishing the journey toward international religious freedom – through community advocacy, smart voting, and individual open-mindedness – is in our hands.

Works Cited

Cong. Rec. 27 Jan. 1998: 1-30. U.S. Department of State. Web. 27 Nov. 2009. <http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/2297.pdf>.

Dawkins, Richard. The God Delusion. 2006. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006. Google Book Search. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Goldberg, Jonah. “An ugly attack on Mormons.” Editorial. The Los Angeles Times – California, L.A., Entertainment, and World news. The Los Angeles Times, 2009. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

International Religious Freedom Act of 1998. 22 USC. Sec. 6401. United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Locke, John. Two Treat

The year is 1620. Under a pallid November sky, dark cerulean waves gently lap against cold sand. Atop dunes, shrubby pines overlook the bare, weathered shore. The day moves slowly, reluctant to expose the sweet wood further inland to the bitter winds of the coming winter. At first glance, it is a typical autumn day: small fish swim about in the chilly waters while the vegetation on shore, swaying with the breeze, seems to cheer on the courageous creatures as they brave the cool waters… But today is far from typical. Beyond a low shoal appear square-rigged sails, and a ship of moderate size interrupts the horizon. As the ship approaches, a face appears, disappears, and then returns with many others. The travelers aboard the ship look like they have been at sea for too long. They are travel-worn, fatigued, and undernourished, yet, even from afar, a strange excitement can be seen, a peculiar enthusiasm radiating from faces that have become accustomed to seeing nothing but ocean. But theirs is something greater, for their eyes behold not only the shoreline of a new home but a harbor for religious freedom. They are the Pilgrims from Southampton, pioneers of religious freedom, and the founders of our country.

Nearly four centuries later, the journey of the Pilgrims’ has long ended, but their torch of religious freedom still lights the path of a longer journey ahead. In today’s post-modern era, scientific innovation is commonplace; democratization and globalization have spread to some of the remotest corners of the world; and freedoms and individual rights hold a solid place on the international agenda. But work still remains to be done. As a fundamental expression of autonomy and free will, international religious freedom should be a matter of consequence to every young American. Ensuring this freedom ought to be a central focus of United States policy because the U.S. government may only claim legitimacy at home and abroad if it enforces existing law; because intolerance in America’s own past demands that we provide for a freer future; and because religious freedom is a central component of our country’s origins and of the philosophy underlying the whole of our government.

In order for the United States government to claim rightful legitimacy to its own peoples as well as other countries on the global stage, it must demonstrate a respect and adherence to existing law. With the passing of the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) of 1998, the U.S. officially declared religious freedom as one of its overarching policy objectives. Furthermore, the U.S. has already acknowledged that “The right to freedom of religion is under renewed and, in some cases, increasing assault in many countries around the world. More than one‑half of the world’s population lives under regimes that severely restrict or prohibit the freedom of their citizens” (22 USC 6401, 1998). In addition, a recent annual report by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) named thirteen countries, including world powers such as China, as “egregious” violators of religious freedom and recommended that these be named “countries of particular concern” (CPC) for their systematic violations of religious liberty (USCIRF Annual Report 2009). These alarm bells call for action by the U.S. Secretary of State as well as by the President himself. In particular, CPC status requires the Secretary of State to pursue “a range of specific policy options to address serious violations of religious freedom” (USCIRF Annual Report 2009), and the U.S. One Hundred Fifth Congress has declared that “The entry into force of a binding agreement for the cessation of the violations shall be a primary objective for the President in responding to a foreign government that has engaged in or tolerated particularly severe violations of religious freedom” (Cong. Rec.). For the U.S. government to disregard its own exhortations and reports would surely weaken its legitimacy; hence, international religious freedom must be maintained as a policy objective.

Not only do the U.S.’s own legal actions mandate a policy focus on international religious freedom, but international law also commands a U.S. initiative in religious freedom endeavors. Presented and co-authored by the U.S.’s own First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) expresses adamantly and unambiguously in Article 18 that “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.” As one of the few countries with a permanent seat on the United Nations’ Security Council, the U.S. has an obligation as a global leader to guide the promotion of the UDHR, so that, one day, its promises can truly be “universal.” With partner countries on the Security Council having been labeled as countries showing marked disregard for religious freedom (People’s Republic of China and Russian Federation) (USCIRF Annual Report 2009), that the U.S. should set a positive, proactive example is even more imperative. Indeed, the fulfillment of this duty is essential for the U.S.’s image as a crusader for freedom and as a government determined to fulfill its own lofty promises; in a way, the U.S. is even committed to act by its status as a ratifying member of the multilateral treaty the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (United Nations MTDSG).

Though the alphabet soup of international laws such as the UDHR, ICCPR, IRFA, etc. are a modern phenomenon, throughout our history we have fought our own battles against intolerance. Considerable progress has been made: America has evolved from a loose association of towns populated by Christian whites to a vast land of religious diversity. Discrimination against religious minorities has decreased dramatically, and the last millennium has witnessed the rise of leaders of myriad faiths, including the first Roman Catholic President in 1961. Nonetheless, vestiges of intolerance still stain the new, progressive face of our country. A California political ad aired as recently as 2008 viciously targeted Mormons and roused public assault against Mormon establishments (Goldberg); and former President George H.W. Bush has stated in a public press conference, “No, I don’t know that Atheists should be considered as citizens, nor should they be considered patriots. This is one nation under God” (Dawkins, 43). These incidents, among countless others, show that the U.S. has not yet erased its past of intolerance and that increased efforts are needed to secure that future of freedom so passionately envisioned by our Founding Fathers.

When the Founders established our government centuries ago, they borrowed heavily from a philosophy of natural rights by the Englishman John Locke. Locke argued for the existence of certain unalienable rights – life, liberty, and property, which all men “hath by nature a power… to preserve… against the injuries and attempts of other men” (Locke). The importance of these principles to our government is evident in the Declaration of Independence, a document centered on Locke’s ideas. When the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Colony in 1620, they brought with them that same spirit of self-determination, which surfaces today as laws such as the IRFA and the UDHR.

It is crucial that, as young Americans, we be familiar with the continuity of America’s passion for individual liberties, for the task of finishing the journey toward international religious freedom – through community advocacy, smart voting, and individual open-mindedness – is in our hands.

Works Cited

Cong. Rec. 27 Jan. 1998: 1-30. U.S. Department of State. Web. 27 Nov. 2009. <http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/2297.pdf>.

Dawkins, Richard. The God Delusion. 2006. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006. Google Book Search. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Goldberg, Jonah. “An ugly attack on Mormons.” Editorial. The Los Angeles Times – California, L.A., Entertainment, and World news. The Los Angeles Times, 2009. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

International Religious Freedom Act of 1998. 22 USC. Sec. 6401. United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Locke, John. Two Treatises on Government. London: C. Baldwin, 1824. Center for History and News Media. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Smith, John. A Description of New England. Ed. Paul Royster. 1616. Lincoln: University of Nebraska – Lincoln, 2006. Digital Commons at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln. Web. 27 Nov. 2009. For descriptive material in introduction.

United States. United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. Annual Report 2009. Washington: n.p., 2009. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

ises on Government. London: C. Baldwin, 1824. Center for History and News Media. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.

Smith, John. A Description of New England. Ed. Paul Royster. 1616. Lincoln: University of Nebraska – Lincoln, 2006. Digital Commons at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln. Web. 27 Nov. 2009. For descriptive material in introduction.

United States. United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. Annual Report 2009. Washington: n.p., 2009. Web. 27 Nov. 2009.