The One Earth Award, underwritten by the Salamander Fund of the Triangle Community Foundation, recognizes four students whose creative works address the pressing issue of human-caused climate change. These students were challenged to create works that advance our thoughts about climate change and our understanding of solutions. Each of this year’s works not only meets the challenge but also inspires readers and viewers to take action and have compassion for their fellow man. For their creativity, each student will receive a $1,000 scholarship.

Congratulations to the 2022 One Earth Award winners!

Gwyn Barnholtz, West Chester, OH

Eli Browne, La Jolla, CA

Eduarda Favero, Boca Raton, FL

Mustafa Haque, Plano, TX

Del Mar, Disappearing

PERSONAL ESSAY & MEMOIR

Eli Browne, Grade 11, The Bishop’s School, La Jolla, CA. One Earth Award

I am a villager in the least noble sense of the term. I don’t live in a hamlet unified by a community church. My home is not one of many dwellings huddled together to provide for the common defense. My neighbors are not producers; we do not fish nor farm. I don’t even live in a rural area—rather, for all relevant purposes, I live in San Diego, the eighth-largest city in the United States. My home, however, is situated not within those city limits, but instead on a two square mile block of land that was carved out of San Diego’s coastline in 1885.

Del Mar is one of two places in the world where the Torrey Pine tree grows. Its northern and southern boundaries are both defined by lagoons. The village boasts three miles of beaches, the second-largest horse racing track in the nation, and the San Diego County Fair. Each year I watch it disappear.

DANAUS PLEXIPPUS

Monarch butterflies, known for their iconic orange finery, cross North America in dramatic migrations every year. In spring and summer, they’re easily found along the northern reaches of the continental United States, covering the country with a belt of fiery plumage. During winter, they take shelter from the cold in various locations dotted across the continent. For western monarchs, that place is California’s coastline.

I was lucky to be able to walk to elementary school. My siblings and I were proud of the independence such a walk entailed; my parents were happy to see us get outside. After school, in order to spend more time with a friend, I’d often take the long way home: first, I’d walk north to his house; then, I’d go around his block and walk back south to mine.

As fall turned to winter, the monarchs’ journey would twirl past mine. My slightly-longer walk gave me more time to admire the migrating butterflies who would come to spend the season with us. Every step on those walks home seemed to be glanced by a tiny bit of apprehension, a pause before each new stride. I looked up from the sidewalk, watching choruses of marigold-winged glory flicker in the afternoon sun. I was enchanted, mesmerized by their sudden bursts of floaty motion in hampering November air.

In three decades, the monarch population in California has declined a staggering 99 percent. My elementary school years posed a perfect window to witness their final demise. Theirs is a departure I’ve felt beyond headlines—I haven’t seen a migrating monarch for the past three winters, save one lost butterfly I witnessed flailing in autumn chill two years ago. I feel privileged to have caught a glimpse of their final passage, to have seen a shade of orange I’ll never see again.

ELEVENTH STREET

I’m no monarch butterfly, but I too have an annual journey oriented by shifting seasons. For me, the time of the trip is every August, and the destination is a crumbling bluff on which I watch summer depart. While short, the trek is precarious—at any moment, a tremor or train or gust of wind could see it collapsing into the Pacific.

In and out, in and out—something draws me to this particular strip of beach, marked in Del Mar by Eleventh Street. Hopping over a poorly-placed barrier, I make my way through gaps and bushes. I scurry across the train tracks running nearby the bluff’s edge, making note of those brave enough to cross without looking. It’s always around an hour before sunset when I reach the edge, and then I slowly make my way down the cliffside, doubting myself each time a shoe slips. I reach the sand. The surfers are usually packing up then—different people, but their faces look the same every year. I love to swim alone until the sun sets; then, I’ll climb the cliffside again and part with the beach until next year’s summer comes to a close.

This beach comforts me with constancy. I do nothing but watch it change. The path narrows every passing summer. When rocks tumble, it makes local news. Trains stop more often now. We wait for cliff failure. The ocean slowly chips away at everything I remember: the coastal train, the picnics tourists have on the cliff’s edge, the wildflowers and cacti, the surfers, the runners, the sand. At high tide, ocean spray splashes against the rocks so passively that I forget the damage it inevitably does.

To Del Mar residents, this bluff is ours. Each of the town’s cliff sides has a political advocacy group attached to it, relentless in protecting these decaying vessels. The proposed construction of a hotel creates local outrage. A plan to fence off the rail tracks, an initiative to protect tourists and residents alike, is villainized by flyers, yard signs, and retirees greeting every person who dares walk down to the beach. A plan by San Diego County to re-stabilize the cliffs, staving off erosion and saving the Amtrak line from permanent failure, is seen as an existential threat.

Despite the efforts of residents, the cliffside won’t endure. No amount of political organizing can postpone a rock finally chipping or an unforeseen seismic event. But these political squabbles have taken on characters of their own, a personality-defining trait of a strong-willed village refusing to concede any weakness or wrong. I don’t like to think of myself as one of the people waiting for the cliffs to fall. Every time I visit them, though, I wonder if it will be my last.

DEL MAR MUNICIPAL AIRPORT

Del Mar is connected to the rest of the world by two major throughways—Interstate Five, a favorite of angry drivers rushing upstate at eighty-two miles an hour, and the historic Highway 101, which snakes along the coast in a slow, meandering fashion. Neither is particularly special, but the empty land stranded between them is to me. There, the San Dieguito Lagoon engulfs miniature fluvial deltas, narrow strips of land shaped by a river bearing the lagoon’s same name. There is a runway on one of these strips, but no plane has landed there in sixty-two years.

I drive up the freeway almost every other day, but I never noticed the lagoon until my mom forced eight-year-old me to go walking with her as part of my fitness goal. We trekked down to the water together, journeying down each wooden dock extending out towards the river. Each dock-end hosted a series of fading information boards. At that point, I discovered the abandoned airport, then a host to flocks of seagulls crowding on its banks. I’ve never been able to forget it since.

Daily flights from Burbank to here used to cost sixteen dollars round trip. During World War II, naval installations built to protect the West Coast teemed with life—soldiers ate, civilians slept, blimps took flight, and trucks ran in and out of town. I imagine every person here was conscious of the water that ran up to each spit of land’s edge, softly rising and falling onto the sand flats. They all knew it as able to flood the estuary with the slightest rise in tide.

Today, the San Dieguito Lagoon feels empty. That’s because it is. Having suffered three droughts over the past decade, the water levels have fallen drastically, leaving behind stark discoloration on the banks where land has only recently been exposed. Vegetation creeps down to an imaginary line only to stop cold in its tracks, brackish water of the past inhibiting any life from flourishing on newly-revealed land.

I like to walk down to the wooden docks that stretch out into the water. One of them is crossable, so much so that I can sit down on the abandoned runway in the middle of the estuary and watch the water recede a few millimeters more. The sound of the freeway behind me is awfully muffled; not even a seagull can be seen in the distance. The silence roars. All semblance of life has since deserted the lagoons that lie on Del Mar’s edges, leaving me the sole witness to their quiet departure.

CREST CANYON

Consistently overshadowed by the nearby Torrey Pines State Reserve, Crest Canyon is frequented by characters of a peculiar sort: small children, suburban moms, golden retrievers, joggers, coyotes, rattlesnakes, and me. None of us really love the canyon, but we can’t be bothered to go anywhere else. Its haphazardness—its old trash cans and dangerous trail sections and bits of animal waste scattered on dirt paths—is what defines it. Indifference lets life flourish, or so I had been led to believe.

I love thunderstorms. I can remember almost every storm I’ve witnessed my entire life, a unique trait of someone who’s never left the desert. Four years ago, for example, a large cold front hit San Diego’s northwestern corner. I welcomed the rumbling of thunder so close by, and I sat by the window until the rain stopped to watch the sky light up in foreign lightning flashes.

One instance of thunder had been extraordinarily loud—just a few hundred feet away, perhaps—and minutes later, I heard sirens. I learned a few days later that the sirens had come not from an ambulance but rather a firetruck rushing to put out a blaze on the canyon’s rugged south end. The bolt had struck one of the older trees, a massive match ready to ignite at any moment, and it proceeded to collapse onto one of the slopes defining the canyon’s edge. Only heavy rain saved the brush from falling victim to California’s next great wildfire.

The fallen tree was initially an object of interest. Straddling a minor trail, I could approach it easily, observing its sheer size and admiring its charred remains. It was a minor distraction, something for hikers to push around or jump over en route to a trail’s end. The trunk has since deteriorated, wood rotting in a lifeless hull, and I know that one day some hiker’s push will entirely dislodge the log from its chaparral-graced bed, sending it tumbling to the canyon floor. I only hope that that hiker won’t be me.

Another storm arrived two years ago, sending another aging tree toppling down. This one, however, hit the most used part of the canyon to conclude a splitting descent. Upon impact, the two main trails collapsed, forming part of a glorious sinkhole I felt lucky to see firsthand. That was, I could see it until a few days later, when the city erected chain fences around it and closed every trail leading towards it. Maybe, at that point, the indifference had ended.

Two years later, indifference still defines Crest Canyon. Despite multiple years of fencing, this trail remains unusable. The sinkhole is wide open. People are told that the canyon is closed for their safety. Once-frequent visitors stay away from blocked entrances, and trails can only be accessed through deteriorating hidden entryways dotting the canyon’s perimeter. Del Mar knows nothing of them. Apathy erased Crest Canyon from both map and mind.

MANAGED RETREAT

Translated from Spanish, “Del Mar” means “of the sea.” Nearly every aspect of the village’s history lives up to this name—the planned out beach resorts that never came to fruition, the naval installations that have since been abandoned, the advertising slogans it still bears today. The village has decided it will die living up to that same virtue.

Del Mar’s policy towards rising sea levels has been described as one of standing ground. Maybe it’s better characterized as the last words of Arachne. One of the first California municipalities to form a climate action plan, Del Mar chose to reject the strategy of managed retreat, defying the advice of planners and scientists alike. Residents insisted that proposed policies would damage both the town’s character and coastal property values. Del Mar will instead hold onto the past, relying on the same aging seawall it’s relied on my entire life. The seawall is remarkably small—easily scaled by a child chasing after a volleyball—and it now bears more responsibility than ever before.

In the face of change, Del Mar has closed its eyes. It is a village desperate to hold onto the things that once defined it, grasping onto relics of the past and refusing to let go. Every time I walk through it, however, I can only notice more differences. In its efforts to preserve the present, Del Mar hasn’t managed to slow the future’s onslaught: residents have merely deferred it to the next generation, content to freeze time for the most fleeting of moments. One of the few things I can rely on to stay constant is the crashing of waves on the shoreline. I know that even when Del Mar has finally finished disappearing, those powerful waves will persist, relentlessly pushing heaps of salty white foam towards whatever remains. If I am to have my way, I will not bear witness to this village’s epilogue. In matters of nature, however, the people of Del Mar very rarely get their way.

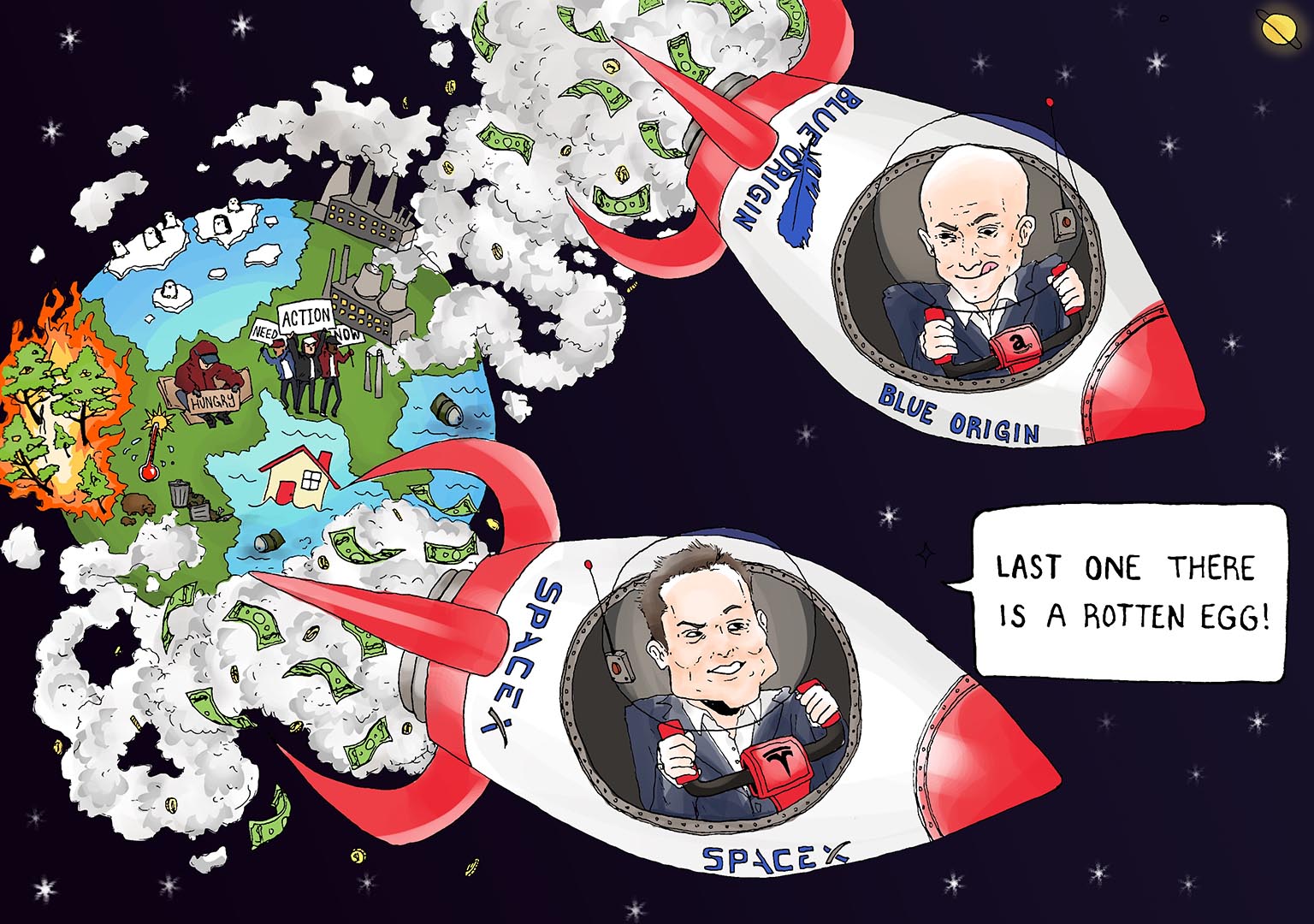

Featured image: Gwyn Barnholtz, The Billionaire Space Race, Editorial Cartoon sponsored by The Herb Block Foundation. Grade 12, Lakota West High School, West Chester, OH. One Earth Award