The Best-in-Grade Award, sponsored by Bloomberg Philanthropies, is given to two works of art and writing from grades 7-12. This Special Achievement Award comes with a $500 scholarship for each student that receives this award. As the name suggests, the works are judged on a grade-by-grade basis, giving students the chance to earn additional recognition among their peers.

Congratulations to the 2020 Best-in-Grade Awardees:

Grade 7:

Harper Golden

Kelsey Gregson

Burton McCulley

Brady Payne

Grade 8:

Fiona Jason

Mirembe Mubanda

Mikaella Spyrides

Theresa Straw

Grade 9:

Amanda Diao

David Du

Logan Furlonge

Eva Shen

Grade 10:

Sara Homma

Yasmeen Khan

Echo Seireeni

Yuchi Zhang

Grade 11:

Victoria Choo

Faith Nguyen

Chiemeka Offor

Katherine Vandermel

Grade 12:

AnnaGrace Brackin

Elizabeth Chan

Debjani Das

Erika Yip

| More Than Muzungu

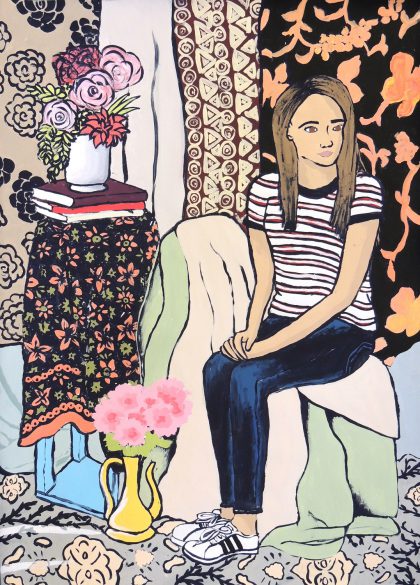

MIREMBE MUBANDA, Personal Essay & Memoir. Grade 8, Fieldston Middle School, Bronx, NY. In Kampala, I sat cramped in between two of my aunties on a small, leather armchair. My relatives peppered me with questions about grades, homework, and extracurricular activities. Until, someone remarked, “Mirembe, you have such light skin.” “You are a Muzungu, mmm?”

“Aw, let her be, look at her father.” “But look at the mother, she is a Muzungu.” “Mmmm.” Immediately, I became shy and started to pick at a crack in the leather chair. In Uganda, I am a “muzungu,” the Luganda word for a White person. But In the United States, I am Black. From a young age I was aware that my father is Ugandan and my mother has ancestors from multiple European countries. Although I am Biracial, for a long period of time I struggled to recognize my European ancestry. Most Americans who meet me, perceive me as Black, influencing in how I think of myself. I, too, see myself as Black, because I have skin the color of coffee with milk and tight, kinky curls. When my Ugandan relatives called me “muzungu,” I used to brush it aside and innocently display my five-year-old smile. Now being called a “muzungu” annoys me, and I recently came to the realization that it touches something deeper: who am I? How do people see me? Similar to Kayla DeVault, I found that “when I was older, the questions came, which made me question myself.” Visiting my aunt, I flip through leather albums filled dusty daguerreotypes. Women in the pictures wear corsets and hats with large, black plumes. Back at home, I lie on my couch and try to memorize a family tree, filled with names with Dutch Jewish names like Elizabeth Boasberg, Hannah Exstein, and Rachel VanBaalen. Who were these women? Did they like to gossip? Did they have favorites among their children? Other days, I attempt to bake a Soda Bread, with a recipe attributed to Honora Wall, who emigrated from Ireland. During these activities, I am able to appreciate my ancestors from Ireland, Austria, and Holland. It reminds me that I am African, but also have European ancestors who have passed down recipes and photo albums. So I am better able to recognize other parts of me, not only the part the world sees. Even when American people see me as Black, they might not envision what it means to be Ugandan. This summer, I visited my eighty-nine-year-old grandfather. Sitting on his back porch, which overlooked the hills of neighboring villages, he told me stories of my distant relatives. I would ask him questions about my deceased great-aunts and great-uncles, and supposedly royal third cousins. Spitting out tart Jambula pits and chomping on crispy, roasted grasshoppers, he would explain how I was related to a solemn-faced woman in a black and white picture, kneeling with a large group of women in front of a mud hut. Visiting relatives, I would often feel excluded as they spoke in rapid Luganda. The words seemed to fly so easily from their tongues, but I would have to repeatedly ask my father to update me on the newest topic of the conversation. One morning, as I sat sipping my freshly squeezed papaya juice, my grandfather’s housekeeper approached me. She tapped my shoulder and handed me a dusty red pamphlet. She explained that it was an English-Luganda dictionary, filled with the translation of many useful phrases. I was ecstatic. For the entire day, I sat on the porch and read the little pamphlet from cover to cover. Later, in the evening, I asked my grandfather to give me a lesson in Luganda. He would say a word, then I would repeat it, and state the translation. While speaking around the toothpick in his mouth, he would correct my pronunciation, and tell me to enunciate the “n” in “nnabo” (ma’am in Luganda). Although many of my family members still call me a “Muzungu,” I try to honor my Ugandan heritage by asking my grandfather questions. In Uganda I am a Muzungu. In the United States I am Black. But I am also Biracial. Now, I am able to ask the questions that help me discover many sides of my heritage, without letting people decide who I am. —————————————————————————– DeVault, Kayla. “Native and European-How Do I Honor All Parts of Myself?” Yes! Magazine, 24 Apr. 2018, www.yesmagazine.org/issue/decolonize/2018/04/24/native-and-european-how-do-i-honor-all-parts-of-myself/. |