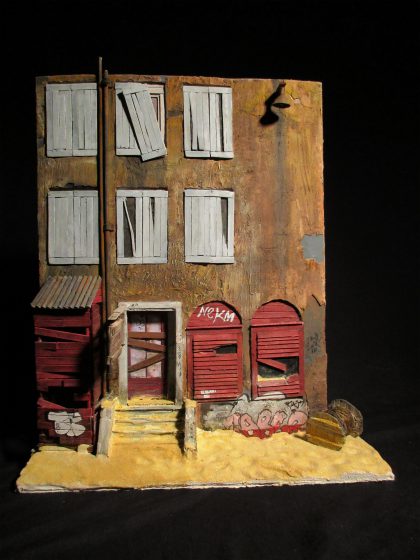

We continue our Eyes on the Prize series with artist Christopher Velez and writer Alexandra Swerdloff. In their works, both explore time. Alexandra writes about things that have happened in the past in order to better understand herself and the world, while Christopher creates miniature buildings whose facades have been eroded by time to evoke a sense of nostalgia.

Christopher Velez

“Oblitus means “forgotten” in Latin, and it is fitting for this collection of works because all of the buildings represented are in a state of disrepair, as if they have been neglected or forgotten. The work is centered around the concepts of urban decay and planned obsolescence. What I try to represent in my works is a strong sense of nostalgia. Although the images and places represented are not specifically places that would traditionally be viewed as idyllic, the distressing gives them a sense of history and recalled memory. The scaling down of the buildings makes them feel both more accessible (like a doll house) and more distant (buildings the viewer can never hope to enter), and the addition of the LEDs gives them a feeling of life even though it would be impossible for them to be lived in.”

Alexandra Swerdloff

“As I reach my final year of high school, I find myself looking not just forward, but back. Back at where I came from—my relationship with my family, the way they’ve shaped me. Back at where my people come from—at the histories of the Jewish and the LGBT communities. Back at the history of my home state—at the forces that make Idaho the home I know today. One of the reasons I’ve always loved to write is because it serves as a kind of time machine. Through writing, I can travel back to the AIDS crisis, the civil rights struggle, the beginnings of the Israel/Palestinian conflict, my early childhood, and any other time period that fascinates me, and through this writing, gain a better understanding of myself and my world.”

Generation to Generation

Personal Essay & Memoir. Grade 12, Age 17, Boise High School, Boise, ID

“Blessed are You, Adonai our God, God of our fathers and mothers, God of Abraham, God of Isaac, and God of Jacob, God of Sarah, God of Rebecca, God of Rachel, and God of Leah.” So reads a portion of the amidah, the Jewish prayer that forms one of the central pillars of the Shabbat service. It reflects one of my religion’s core beliefs: that of l’dor vador, generation to generation. The belief that we owe something to those who have come before us. When we acknowledge our ancestors, we recognize that, no matter how difficult our passage, others have already walked it. It is a humbling assertion–and also a comforting one. In studying the stories of our ancestors, we gain courage. They provide us with a path to follow.

I have found these paths in the usual places–between the walls of my temple, in the pages of the Torah, in private times of prayer. But I have ancestors besides Abraham and Isaac, and they have come to me in less conventional ways.

My ancestors hide in the Dewey decimal system; they are the rainbow-colored books laid out in the display case for Pride, the section marked ‘Gay/Lesbian’ in the library. Some of them are famous; others are strangers, like the two dads I see playing with their daughter at the playground, or an elderly woman marching in a Pride parade. They have names like Harvey Milk, Sylvia Rivera, Alison Bechdel; in their varied stories, I see echoed versions of my own. I find comfort in their footsteps alongside mine.

When I began to think that I was gay, my main concern was not that I would be rejected by my family, who had always made it clear they would support me no matter what. I wasn’t even that preoccupied with being rejected by my friends, although that was one of my worries. No, my biggest fear, the one that surfaced in every conversation I had with myself about the topic, was the loneliness. I didn’t know many gay adults; I had no idea what my future would hold if I did this terrifying thing. Could I still marry and have kids, like I’d always dreamed of? Could I still be the star student and good kid I was before? Could I handle possible rejections from friends?

When I worked up the courage to search ‘gay/lesbian’ in the library database, I took the first step to finding the answers to my questions. The Boise Public Library is not exactly known for its huge selection of LGBT literature, but to my uninitiated eyes, the number of books on the shelf I was directed to was overwhelming. I piled up my arms with titles that would soon become staples on my bookshelf: And the Band Played On, The Mayor of Castro Street, Boots of Leather / Slippers of Gold, Fun Home. To me, they became like the siddurim I clutched on Friday nights; within their pages, the story of my people was written. I learned about the AIDs crisis, lesbian factory workers during World War II, the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society, and through my reading, my confidence in my sexuality grew. I could see myself in these pages; they told of outcasts and rebels, but also parents and lovers and artists. Some were all of the above. And the more I read, the more I realized that perhaps being one of the outcasts or rebels wasn’t so bad. One could fit stereotypes and still be the kind of brave, compassionate person I looked up to. Sylvia Rivera was a drug-addicted sex worker–and an activist who saved young trans women from the streets. Harvey Milk was promiscuous and loved theater; he also championed some of America’s earliest LGBT rights legislation. Their nuanced stories helped me come to terms with my own. Like them, I contain multitudes. I have short hair and scorn dresses in favor of a t-shirt and jeans; I also hate sports, cry easily, and want to start a family someday. You could reduce me to words like butch or dyke, or you could say I don’t fit gay stereotypes at all. Both assumptions are too simple. They do not do justice to who I am as a person.

I don’t know if I will end up doing something with my life noteworthy enough to record in the annals of history. I have no idea if someday, a questioning kid with countless fears swirling in her head will pull a book down from a shelf marked ‘LGBT History’ and find my name in its index. I don’t know if she will see herself reflected in my story. I certainly hope so. All I know is, whether I’m a famous name in a history book or just a mother with her wife and kids in the playground, I will keep giving the gift my queer “ancestors” have given me. By living my life openly and proudly, I add my pair of footprints to the ground. The path I have followed joins the others, and I pass my story down: l’dor v’dor, from generation to generation.

In the quiet moment for personal prayer that follows the amidah, I have taken to adding my own ancestors’ prayer. Blessed are you, Adonai my god, God of my fathers and mothers; God of Harvey Milk, of Sylvia Rivera, of Marsha P. Johnson, of Storme DeLarverie. Of all outcasts and rebels and weirdos, past and present. Blessed are you, God of the thousands dead of AIDS, of the butches and femmes of the 50s; God of the proud and the closeted, those who told without being asked and those who kept their lips sealed tight. Bless my ancestors, bless me, and bless those who are to come after. Bless all future kids, trans and gay and bi and questioning, standing in libraries and in darkened movie theaters, looking, for the first time, at a story like their own.

May my own path guide the way.

To see more Gold Medal Portfolio recipients, past and present, visit our Eyes on the Prize series.