Next up in our showcase of the 2020 Gold Medal Portfolio recipients are students Charles Rounds and Emory Brinson. Charles uses his artwork to show how religion has affected his views of success and ambition. Emory, through a complex series of elegies, addresses her feelings about love, loss, religion, and cultural identity.

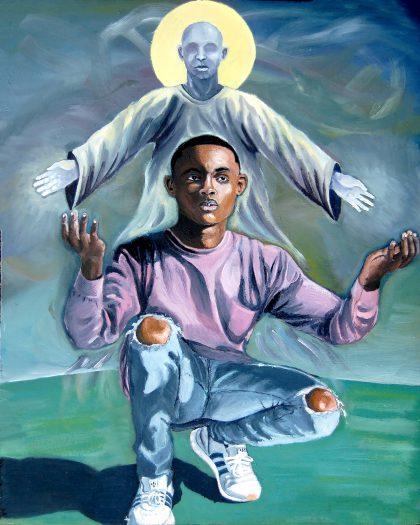

Charles Rounds

“Through my art, I illustrate how prayer and faith have caused me to use my hands as a manifestation of drawing what I believe can happen, into existence. The bible talks about faith being the substance of things hoped for and the evidence of things not seen. Through my art, I exercise my faith in hopes of conveying to all nationalities that if you truly believe in something, you can achieve it.”

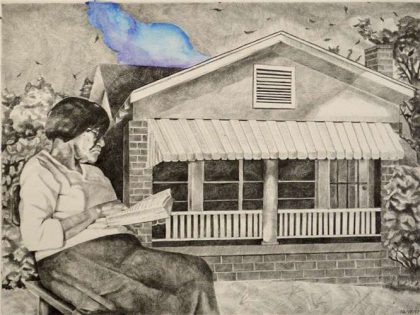

Emory Brinson

“In these words, I hope readers will find compassion and understanding; I hope they will feel my sorrow, my joy, my heartache, and my anger. Most of all, I hope they will come away challenged to move towards a better, kinder world, one where hope, not fear, reigns supreme. This is A Study in a Lifetime of Elegies; this is my origin story – my genesis.”

A Study in a Lifetime of Elegies

Personal Essay & Memoir, Grade 12, South Mecklenburg High School, Charlotte, NC. The Maurice R. Robinson Fund Writing Portfolio

| I. In which I mourn the living.

On September 6th, 2018, Botham Shem Jean dies after an off-duty Dallas police officer illegally enters his home and shoots him twice. The story settles into my veins like ice, and it is all too easy for me to picture his terrified face as he is startled by an armed intruder, only to die at her hands. I try not to picture my uncle or father in his place, instead, I watch my mother react to the story. I can see past her painted concealer mask, and like all black women, she harbors an aching sadness for her brothers, husbands, and fathers. To me and her, it seems like death is always one step away. I’ve been waiting for my father to die since I understood what it meant to be black in this country. Have you ever mourned someone who was still living? It isn’t like watching a trainwreck in slow motion. This is an endless funeral. They roll the caskets out one by one, and my dreamscape is painted in black hues. I wake gasping with the image of my little brother laid in white burning in my eyes. Open casket funerals have been in style since Emmett Till’s mother told the mortician to show the world what they did to her little boy. There are no secrets anymore, and the camera flashes hold the locks open anyway. I look into the mirror and wonder what I am supposed to see. Do my full lips and natural hair tell a story of danger or call into question my intent? I look at my father and try to look past his kind heart and iron-clad morals to see what they must find at first glance. I take in his powerful shoulders and calloused hands, and for the first time, I wonder if people look at him with fear. Suddenly, I am terrified of losing him to the preconceptions in their heads. Why can’t they see what I do? There is an ache that wraps itself around my ribs; it is a constant noose of loss. For the first time, I can see the fearful beast that bares its chest in the place of a person. Understand, this country is committing men to death by prejudice and perpetrating genocide on a systematic level. I have mourned more men in my 16 years than I dare say most will lose in a lifetime. I wait for a day in which children will not have to know this heartbreak with frantic breaths and a mess of tangled veins in my chest. II. In which my father and I come to an understanding. On a Friday night in December, we watch Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing. I ignore the discomfort watching the police beat Radio Raheem to death with popcorn grease on my fingers causes me. As the credits roll, I catch glimpses of my father’s childhood between the black and white text, and his desperation for us to watch this movie finally makes sense. For the first time, I can see him in his true form. His New York accent has faded after 25 years in the south, but there are parts of him that are straight from the rough streets and cramped bodegas of his hometown. It’s in the way he pronounces coffee, the heavy set of his shoulders, and the way he is undeniably straight out of this film. On the screen, the character DaMayer tells Mookie in a Brooklyn accent almost too thick to understand, “Always do the right thing.” My father, for better or worse, has always lived his life by this rule; he is protective of his pride and family, never strays from his perception of the “right” thing, and is a stickler for fair treatment. There are some principles that ingrain themselves into your bone marrow and shape all actions you take from there on out. If I peeled back my father’s thick skin I would find those words burned into the white of his bones. I know this to be true in the same way that I know the sun will rise in the morning. He turns up the stereo volume while we drive past a group of policemen, the words, “F**K THE POLICE” blaring out of all four open windows while we speed by. I’m horrified, but the story he tells me afterward shifts my worldview once again. He’s not quiet or ashamed as he unravels the memory, because my father never is, but I can’t help but wonder if that is the New Yorker in him, or if he was simply born with an unwavering spine. He paints a picture of a little black boy growing up on the outer edge of New York City in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Raw emotion courses through his voice as he tells me about the police pulling him over on his bike in 8th grade. I can imagine him with a painstaking clarity, only 13 but terrified he wouldn’t make it home for dinner because someone decided he didn’t belong. I ache for him, and I am reminded of my own brother, who looks so much like what my father must have at that age. It isn’t until after Botham Jean that he tells me another story. He describes trying to unlock his door as a college student in upstate New York, only for an NYPD officer to tackle him. The policeman calls for backup, and within minutes six police officers are arresting him for trespassing on his own property. Yet again, I am learning to understand my father in ways I could never have imagined. His distrust of the police is one that has blossomed from years of prejudice and attacks. Though I can’t always agree with him or his methods, I can understand on an intrinsic level where that pain and hurt stems from. In the days after I first watch Do the Right Thing, I see the parts he tried to leave behind. New York didn’t make him, nor did his experiences with law enforcement, but both have shaped him in ways I can only attempt to understand. III. In which I find out what it means to exist in this country while black. I have always known that being black in America inherently meant being viewed as dangerous. Every day passes like a hunt in the desert of our distant home. This is predation on a big city scale, and they have turned me into prey. The knowledge is passed through the generations: blowing into my mind with the faint bellow of a slave ship’s horn, and the stench of sweat wafting from the fields. Every people must pass down something to the new generation to preserve the years of history that have built them up from the black soil of a shared homeland. For me, it is the image of my great-grandmother, holding tight to her son and begging with harsh words and soft hands for him to stay out of trouble as the radio blared about that boy who was lynched in Mississippi. The memory has always existed in my mind, smudged with the inconsistencies of old stories, and somehow smelling just like the bitter salt of chitterlings. Two black men are arrested for sitting in a Starbucks without purchasing anything, and the incident becomes the spark to a Twitter firestorm. It seems like every day that social media is popping up with another “Living While Black” Moment. White women and men have been calling the police on black people living their lives for as long as they have been able to, but now instead of silently suffering the uncomfortable consequences of being born black, the victims were taking to Twitter. The stories that go viral act as a window into the harsh realities that had previously been shoved under the rug that is the privilege of white ignorance. There is a difference, however, between knowing that these things happen and watching a video of a white woman screaming for the police to arrest a little boy for selling water. The situations usually resulted in a slap on the wrist with no harm done on either side, but it begs the question: how much anguish can the Black American psyche take before the constant insinuation that they are less than starts to sink in? The sweltering summer of 2018 bleeds into the sharp chill of Autumn, and I find pieces of myself among the bright orange chrysanthemums my neighbor plants. The day after the flowers bloom, the moving sign in her yard gets a shiny new addition; a plaque swings in the wind and the word SOLD sinks into my stomach like lead. The moving trucks blew in with the first jack o’ lantern, and with it came a growing nervousness in my mother. The new couple was likely nice enough, but the images of the innocent black children splashed across Twitter were still fresh in our minds. “I’m going over to introduce myself and make it clear that 5 black children live on this cul de sac. I don’t want there to be any confusion about who belongs in this neighborhood.” The subtext isn’t subtle: she wasn’t going to let these new neighbors treat us as if we didn’t belong, and there was no telling what kind of assumptions could be made from a quick glance while we stepped under the streetlight on the way to the bus stop. Other people hoped to make nice with the new neighbors to avoid complaints about loud Christmas parties, but my mother wanted to make sure they knew we belonged. She was saying, “Look. These are my brown children, and they live here, just like you.” This is our persistent reality; a life of constant motion, always watching for the next predator who waits in the pale brush, preparing to pounce. IV. In which I discover that differences lie deeper than skin. Growing up, I often longed to be more like everyone around me, but I never felt more like an outsider than at my middle school. That wasn’t always the case. In fact, for the most part, it was a positive experience. I learned an abundance about the world and myself from my teachers and classmates, but one thing they never needed to teach me was that I wasn’t like them. Being one of three African American girls in the grade left me with the constant knowledge in the back of my head that, as much as I tried to blend in with my classmates, I would always be different. Most of the time it remained in the background, but other times I wore it like a bleeding brand. I bore the nervous looks during slavery and civil rights units, tried not to roll my eyes when at least fifteen people congratulated me after President Barack Obama was re-elected in 2012, and quietly acquiesced to reading off black history facts. On August 9th, 2014, Michael Brown is murdered, the Black Lives Matter movement emerges from the ashes of the burning buildings in Ferguson, Missouri, and my world shifts on its axis. I struggle to come to terms with the idea that there is violence affecting my people in a way I haven’t truly understood until this point, but the other kids are angrily protecting the police. They scream “All Lives Matter” and spit when they dare to say his name. In those familiar halls, Michael becomes synonymous with thug, and I learn to walk with my head down. They act as if he isn’t worth the same amount of space they are, and by association, I suddenly wonder about the amount of room I take up on the stairwell. They look to me with expectant eyes, but what can I say in response when I see him in every family photo that hangs on our wall? When I look in the mirror? I was floating alone in a sea of people who didn’t understand how close to home a shooting 724.1 miles away could feel, and the loneliness was beginning to eat away at my sparkling worldview. V. In which I am learning how to not be afraid. I am no stranger to fear. It has taken the shape of maggots to eat away at my insides since I learned the difference between denotation and connotation. In these terms, the space between what black means and what this country hears instead is big enough to hold a slave ship worth of bodies. I am terrified of watching my family die at the hands of a nation that doesn’t care about them. I am afraid of losing myself in the mass of people who cannot help but see me as less than, who can never understand what it means to exist as a black woman in this country. Still, I am slowly learning how to turn fear’s shape into something more. I have spent a lifetime studying the elegies that define the lives of girls that look like me. We live, trapped in the grip of injustice and death. Every day we are threatened with the stench of terror, waiting around every corner to remind us of our place. Still, we have a choice. There is loss all around us, yes, but there is also joy. While videos of police brutality circle the internet, inspiring messages of hate and disgust and reminding us that we are in a world that sees us as inferior, so are images of women with broad hats, waiting to serve hungry children with warmth and love. Even as I feel compelled to write elegy after elegy, wracked with fear of the future and sorrow from the past, I recognize the opportunity to write odes and sonnets in honor of the men and women who inspire everything I do. Every day, I find myself celebrating our durability. Here there is fear, and here there is love. This is my pledge: I will elegize and mourn and dig into the melancholy sitting heavy on my mother’s shoulders, and yes, I will fear, but I will also move this world one step closer to understanding and compassion and overwhelming love whenever I can. I have the opportunity to bring understanding to the people who want to learn, and I have the chance to grow myself. Maybe this realization, the recognition of the complexity of our world, is the distinction between girl and woman. I am still learning what it means to exist as a sister in this country, but what I know is this: the time for mourning is over. This is not the age of fear, but instead resilience. Like my mother, I stare down the world and I say, “Look, we are here, just like you.”

|

To see more Gold Medal Portfolio recipients, past and present, visit our Eyes on the Prize series.