Part 2 of our series on the 2019 Gold Medal Portfolio recipients continues with artist Haoran Xu and writer Sandra Chen. Haoran’s pieces mix the future and the past to create new worlds and possibilities, while Sandra focuses her writing on the issues facing women today.

Haoran Xu

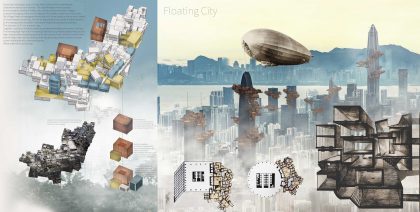

“I seek evolution in human history and cultural legacy. From the Chinese cultural evolution to industrialization and the demise of the authenticity of faith, there lies an irony in human endeavor. Yet the merit, as well as the comical aspects of human society, continues to shape our understanding of the world. So I take the chance to find the future of architecture based on historic social structures and to express individualism in the context of concrete jungles called cities.”

Sandra Chen

“This portfolio is both a reflection and a call to action. I hope (w)om(e)n promotes greater empathy and understanding, encouraging readers to consider the complexities of the young female experience on a deeper, more personal level. Moreover, in the current context of the #MeToo movement, I think female-driven stories are especially necessary to counter systemic societal inequalities. I hope my portfolio can play a small part in this change, helping young women empower one another and realize that their stories are just as real, valid, and deserving.”

Maybe We’re Okay

SANDRA CHEN, Short Story. Grade 12, Amador Valley High School, Pleasanton, CA

Stomach-down on a pillow and hunched-back against the headboard, our bodies bend around each other. Ada’s busy sinking into her Art of Problem Solving book, her fingers resting against her lips, integers oozing down her tongue. Meanwhile, I’m slipping into a consciousness that is not my own, submerged in words that are heavier than anything I know. It’s quiet, but there’s a rhythm in the scratches of graphite tips and the clicking of plastic keys, the little quips back and forth between strokes.

“What’s the cube root of 1728?” Ada asks, her words muffled between teeth and nails.

“What’s a synonym for I’m-not-your-calculator?”

“Smartass.”

I laugh, and we fall back into the kind of silence that is anything but empty.

The truth is, I have never understood Ada’s love for math, with its rigidity, its repetition, its sharpness of angles and edges that cuts right through me. In school, I shove numbers and formulas down my throat and try not to choke; she drinks them like honey, sweet and sticky.

Ada has never understood my love for words. Poetry is too flowery for her, too messy, too many little words hiding deeper meanings, or else too many big words without one. She crafts her words slowly, meticulously; I have learned how to swallow them and embrace the burnt aftertaste.

I’ve talked about it, about us, with my therapist, Dr. Frey. She says that numbers are Ada’s anchor, the constants she relies on when everything else changes, and that words are mine, the release I turn to when my brain won’t stop screaming. I think she’s right, that deep down, Ada and I are the same. Ada needs the clean-cut world of numbers, of strict rules and postulates, of numeral realms in which there is always a right answer; I need the shards of language, the downpour of words across a page, the freedom and power of both creation and destruction. Sometimes she thinks the only problems she knows how to solve are the ones plastered in the pages of her textbook; sometimes I think the only life I can control is the one constructed in the taps of my keyboard. The truth is we are both drowning, and somehow we have become each other’s gasping breath.

These days, Ada spends more time at my house than she does at her own. The change was so natural I hadn’t noticed it at all, like that story about a frog slowly boiled alive. Ada once told me that the premise of that parable is entirely false, that according to modern scientific sources, a frog’s thermoregulation prevents its gradual death. I still like the metaphor.

I’m not sure if I’m the frog in this case or she is, or maybe we’re both immersed in the water together. All I know is one day she brought her history textbook over, the next her English, then her statistics, and now they are all lying flat on a shelf that she occupies alone. The room is becoming as much hers as it is mine, her half-used papers and charger cables splayed across the floor along with my own, a spider web of which we are both producers and prey.

I hear the zipper of a backpack and turn to see Ada roll off my bed. She walks to the far end of the room, careful not to trip over the wires she no longer brings home, and stops in front of the glass. The past few nights, she has taken to escaping through my window so as not to disturb my parents.

“I should go.”

“Oh. I’ll see you tomorrow.” I pause, and as she reaches for the latch, my mouth unlocks. “You can stay, you know.”

“I wish I could,” she says simply, and I don’t push. We’ve never talked about the reason she stays later because we don’t have to. I’ve known Ada almost all my life, know her well enough to read her chipped nails and cut lip to mean her parents are fighting again.

She shakes her head, a humorless laugh fogging up the glass, guttural in a way I haven’t heard it in months. “He’s drinking more.”

I’m not surprised, not really, and I want to say I hate him or Don’t forgive him again or Will you be okay? but all I can manage is “I’m sorry.”

“I have to make sure he doesn’t kill my mom in the morning. Or himself.” Her tone is too nonchalant, her back too straight as she looks out the window toward her own house two blocks down.

“Worse than last time?”

Ada nods.

“Shit.”

Last time was over a year ago, when Ada’s dad was drunk as often as he was sober. He had nearly hit a pedestrian while Ada was in the car, and her mom had threatened to leave him unless he went back to AA meetings. He did, but I guess they didn’t work this time. They never did for long.

“I should go,” she says again, but doesn’t move.

“Be careful. It’s dark out.”

She nods once more, dragging her fingers across the panel before her, carving clear lines into gray-white condensation. Seconds like minutes pass before Ada finally pushes up the window, adding a stream of biting air and subtracting her body from the room. I fall into the bed, my body sinking into the crevices she’d left, and watch her solo silhouette wander deeper into the expanse of midnight.

It’s 7:54 according to the classroom clock, which means it’s been five hours since I woke up. Dr. Frey says morning anxiety is perfectly normal—something about cortisol and low blood sugar levels—but I’m not sure what’s normal about watching the dashes on my bedside clock light up for two-hundred minutes, my back stained with sweat.

The bell sounds like the alarm I don’t need, but when Mr. Morrison stands with a stack of papers, I’m the one ringing. My knees hit the underside of the gum-laden desk, fingernails strike the already-scratched wood. I tell myself it’s the AC, and I think back to Ada’s calculation in freshman year that the school could save up to $1.9 million if it set the thermostat in each classroom two degrees higher. I didn’t understand the math any better than I do my body now.

The graded essays float down around me, one by one, sheets of white dotting desks. Like snow, perhaps. Fragile papers, melting faces. When Mr. Morrison stops at my desk, I catch my essay with blue-veined hands, trace the red scrawl at the top of the page.

You are able to hone in on the key details and organize them logically, and you clearly have a grasp on grammar and mechanics, but your writing has no voice.

The compliment is cold. Twenty-four words of praise are erased with three little letters. There is always a but. I reread the last clause. Your writing has no voice. Again. No voice. Again, again, again, until I can’t hear anything but the voice in my head, screaming, loud, too loud.

SHUT UP, I scream back it, and I almost don’t notice when the classroom falls silent, startled eyes staring at me, glaring at me.

I’m back in my room, or maybe I’m not. Words are swirling, voices reverberating, my head the wreckage of a storm it created. I’m sitting at a white page, and I want to fill it up, have to, need to. But my trembling hands hold too much blood, and all I see is red spilling over black words, hear the waves crashing like a tsunami, loud, too loud. I slam my palms against the keys, send a string of letters flying down the line, tumbling, plunging, click-clack, all that noise. Ada looks over at me, concern flickering in her eyes, eyes staring at me, stop.

“You okay?”

Eyes, no eyes, I don’t want eyes. “Spiders,” my mouth says, exhales, chokes.

They are spiders, not butterflies, never butterflies like everyone says, Ada knows, they have always been spiders to me, hundreds of them, crawling through my stomach, my arms, my legs, black, fast, wild, spinning, webs closer, closer, too close to my throat.

“I can’t breathe,” I gasp, words caught in a silk lattice, constricting, convulsing. “Can’t breathe. Can’t breathe.”

“Hey, hey, you can. It’s okay. You’re okay. I’m right here. Breathe on my counts, okay?”

Ada’s hand on my back, I inhale, 1-2-3-4, exhale, 5-6-7-8, feel my spine expand, 1-2-3-4, feel her pulse with me, 5-6-7-8. I break down my breathing, make it voluntary, conscious, still conscious of Ada’s hand, gentle and caressing. Shallow breaths and heartbeats sync, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8. Air enters and leaves, Ada stays, and I survive.

It’s late at night, or almost morning—I’ve never understood time, how a new day starts when the city falls asleep. I remember Ada once saying something about cyclicity and uniformity and equidistance, but all I know is that time lasts longer in the early hours of the a.m., when the sky bleeds to classic monochrome.

Ada is lying on my bed, staring at the ceiling, as if analyzing the shapes in the stucco. It’s like indoor cloud watching, and I’ve done it too, my favorite being a spot in the corner that resembles a monkey on the back of a fire-breathing horse. The word for why we can see those images is pareidolia, the tendency to look for recognizable patterns in random data. I like the way the syllables curl my tongue, and I think pareidolia sounds a lot like math, and like me.

“Do you believe in love?”

Ada says it so soft that I’m not sure she said it at all. It’s not the kind of question that can be left hanging outside the lips, so delicate it might dissolve in the seconds that pass. “I don’t know,” I say. “I think I’d like to.”

“Why?”

I laugh, because it’s a dumb question, because it’s not really a dumb question, but I can’t answer it, so what does that make me? I counter the only way I know how, the lilt in my voice acting as both sword and shield. “You don’t want to believe in love?”

Ada shrugs, and I notice for the first time how small she looks, her body barely pressing into the mattress. In the silence, our thoughts weigh heaviest.

“Love’s not like math,” Ada says at last, her words drifting like wisps of wind. “You can’t trust it.”

I think about it. There is no formula for love, no postulate to prove, no patterns to follow. Math is neat, love is messy, and I wonder what it means that I’ve never been good at either. “I don’t think it’s love you trust. It’s each other.”

She sits up, looks out the window toward the same spot as always, never able to escape a home she doesn’t want as her own. “What if you can’t trust anyone?”

It is too raw, too sharp, edges of her words cutting my tongue. So I don’t say anything, just sit beside her, hold her hand. Skin against skin, flesh against flesh, I tell her I trust you and I love you, and when she squeezes back, I know she’d heard me.

Weeks later, we’re on my bed together. It’s late and I’m tired, my head inches away from using the calculus textbook as a pillow. Ada is trying to explain to me how integration is essentially the inverse of differentiation, but that the integral of the derivative is not equal to the derivative of the integral. My mind’s spinning and I think I’m starting to see shadows.

“Can you turn on the light?”

Ada rolls over and stretches her hand up to hit the switch, the sleeve of her sweater riding up with it. The lamp shines against her forearm, casting its light onto jagged lines etched into bruised skin. It is too bright. Short, red lines, protruding. Serrated flesh.

The raw slashes almost glowing. Too bright, breathe.

“What did you do.”

I can feel myself form the words on my tongue and dislodge them from my throat, but I do not recognize the voice. It’s visceral, somehow, rough and splintered like rotting wood. But the four lines on her wrist—those lines are rigid, sharp, clean-cut.

Ada traces my eyes down, grabs the cuff of her shirt, pulls it—

“Don’t.”

She stops, withdraws her arm from the light, lets her sleeve fall with gravity. The silence is chiseled, honed, straight to the bone.

“Why.” My questions aren’t questions, I don’t want the answers but need them.

She opens her mouth, closes it, opens it again. “My parents…” she trails off, and I let her collect her thoughts as mine simmer, everything under the surface colliding, burning. “It’s bad. I’ve never heard them fight like this before.” She breathes but I can’t. “I just thought, maybe if I had it on my body, I could take it off my mind. Like, solving by substitution, I guess.”

The sound that spills out of me is laughing, choking, screaming. “Goddammit Ada, not everything is math!”

“I know,” she whispers, and her voice is empty but I am overflowing. “God, do you even hear yourself? You’re so obsessed with your perfect little numbers and equations, it’s like you’re not even living in the real world. Get it through your head, Ada, pain doesn’t follow the fucking transitive property!”

The words bubble out of my lungs all wrong. Ada recoils, rolls her body into shaking arms, wrapping fabric like gauze.

“I’m sorry,” I breathe, but what I mean is I’ve thought about it too, more than you know, but I’m too scared of pain and now I’m scared of losing you because I’m a coward and I’m selfish and “I’m so sorry, I didn’t mean—”

She shakes her head. “You’re right. It didn’t work. The pain didn’t transfer; it multiplied.” She pauses, her fingers tugging at the loose threads near her wrist, her lips fraying at the seams. “You always said I was a masochist.”

I don’t reply, because I don’t know how, because I’m thinking that love and pain are supposed to be inverses, but that the love of pain and the pain of love are far from the same. So I hold her, chest to chest, feel her heartbeat against mine, listen to all of the blood still roaring inside her veins.

Ada is sitting up today, back pressed against the wooden headboard, eyes wandering out of focus. She’s been quiet since morning, and it’s not the usual kind, when she drifts in and out of calculations. Her shoulders are taut, but her nails are cut, and I can’t read her like I want to. I watch her watch her mind, wonder what’s playing behind her lids. “What are you thinking about?”

She doesn’t respond, doesn’t even look up. I’m not sure if she heard me, and I think about asking again when she says, “My mom told my dad that she’s getting a divorce.”

My mouth runs dry, all words withered on my tongue, so Ada keeps going. “She’s already contacted an attorney. I think it’s real this time. I think she’s really leaving him.”

I still can’t speak, can’t think anything but divorce divorce divorce is she okay. My eyes flit toward her wrist for just a moment, find it covered by an oversized sweater.

“I didn’t. And I won’t.”

I don’t meet her eyes, but something in her voice is so honest it’s bruising. I swallow. “Are you okay?”

A beat passes, then two. “Yeah,” she breathes, and I believe her.

I believe her because she is bleeding and I am suffocating, but we are still here. Because maybe we are the frogs in heating water, but we will jump out when the time comes. Because maybe our lives are just random data, but we are still searching for the patterns we need. Because maybe we are the snow and that makes us fragile, and maybe that’s okay.

Dr. Frey says I rely on metaphors because they’re easier to stomach, because they allow me to look at my life without looking within myself. I know she’s right, but I’m learning. So when Ada decides to stay that night, when we are lying on my bed together, two indentations side by side, I think about who we are, not what we maybe are—two girls, a mathematician and a writer, opposites and the same, hurting and loving and being.

To see more Gold Medal Portfolio recipients, past and present, visit our Eyes on the Prize series.