The Gedenk Award for Tolerance is given to students whose works examine their personal role in cultivating acceptance and tolerance in the world. Through our partnership with Grammy Award–winning artist Miri Ben-Ari and her organization The Gedenk Movement, the 2017 Scholastic Art & Writing Awards recognized three writers and three artists for their works reflecting on the importance of increasing tolerance to safeguard a peaceful society. Along with their award, each student will also receive a $1,000 scholarship!

Meet the 2017 Gedenk Award for Tolerance recipients:

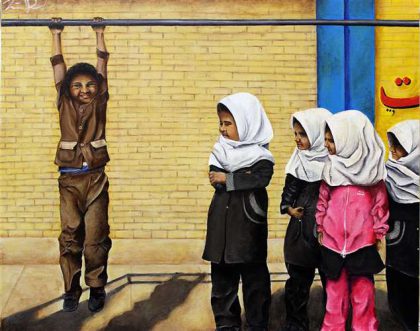

Nasim Dalirifar is in Grade 12, Age 17, and attends Hebron High School in Carrollton, TX

“My reference photo captured a normal split in daily Iranian life. Boys, and later men, are allowed many freedoms that most women can only dream of. While my piece does not provide a solution to this problem, it does shed light on it, and I feel that for a problem to find a solution, we must be able to see there’s a problem.”

Anlan Du is in Grade 11, Age 16, and attends Phillips Academy in Andover, MA

“When writing this essay, I set out to create a lens for my observations of intolerance against those who are closest to me. Eventually, as I pondered the overarching theme of the words which those who suffer intolerance cannot say, I arrived at my metaphor of cherry pits, which encapsulate this enduring and painful silence. I hope that through these personal stories and the ways in which they affected my loved ones I can demonstrate how intolerance can affect lives not only on a broad, visible level, but also on a much more individual and unseen level.”

Excerpt from Anlan’s Personal Essay & Memoir “Cherry Pits”

As I stared up at my parents, wide-eyed, over-pronouncing my words and smiling too much, the remains of the cherries I had stolen lay hidden behind my teeth. After years of practice, I had perfected the art of stealing my favorite fruit from the fridge without my parents’ noticing, but a single flaw in my execution remained: the cherry pits. Unable to swallow them, I instead tucked them behind my teeth, hoping my parents would not see the damning evidence as I snuck by them. Growing up, I pulled this same trick over and over, telling the same lie each time: “I didn’t eat the cherries.”

When my father tried to hide his Chinese accent he often reminded me of that cheeky, seven-year-old me trying to speak through a mouthful of cherry pits, like there was something in his mouth but he did not want anyone to know it was there. Whenever I accompanied him on grocery store trips or visited him at work, he was genial but stilted, affected with vaguely British mannerisms he had picked up while learning English, the picture of a successfully acculturated immigrant. I was too young to understand xenophobia and homophobia and all the other phobias in the world, so all I knew was that his half-hidden accent sounded funny.

At home my father would play CDs of instrumental Chinese music and, smiling, beckon me over to his laptop to show me videos of Olympic swimmers and divers, “Anlan, come see him. Look how fast he is. He got gold, you know.” They were always Chinese. I always wondered why he never played his music at work, never crowed to his co-workers about the Chinese diver who had just won gold the way he did to me.

Then we learned about the Japanese internment camps in school and I learned the meaning of the word “chink” and then I did not wonder anymore. He did not hide out of shame or disdain for his home country: I saw the nostalgia in his eyes when he heard the Chinese national anthem, the pride that shone through even though he was thousands of miles away. No, he hid because when he told people he had emigrated here from another country, the only word they heard was “other.”

Rachel Jibilian is in Grade 12, Age 18, and attends Emmaus High School in Emmaus, PA

“My family originates from Armenia, so the Armenian Genocide is a personal event to us. The Ottoman Empire’s desire to conquer Armenia & slaughter their people resulted in the murder of 1.5 million Armenians, including the father & brothers of my great grandmother who escaped to the United States in 1922 as a young teenager. Although this began over 100 years ago, it has never truly been resolved. Turkey as a nation still denies that it ever happened, leaving families still scarred & justice unserved. Even the United States refuses to acknowledge it, and this personally affects my family. The Armenian writing and necklace I’m wearing in the self-portrait shows my pride of being Armenian. This art piece represents the violence of the Armenian Genocide and how the issues of justice and respect for people of different backgrounds are very important to me. Despite today’s unresolved differences and denial of what happened, we as a people will not stay silent.”

Suzan Kim is in Grade 12, Age 18, and attends Bergen County Academies in Hackensack, NJ

“In my piece, I talk about why it’s important to be open to other cultures by intertwining the story of the Wari population, an indigenous group of cannibals that once lived in Brazil. Similar to the way I was harshly judged for identifying with a culture that consumes dogs, the Wari’ were pressured to conform to Western standards of mourning. We can learn an important lesson about tolerance by reflecting on the Wari’, a group that suffered despite the fact that their traditional funerary practices were not only peaceful, but actually very beautiful.”

Excerpt from Suzan‘s Critical Essay “My Single Story”

On the shores of the Pakaa Nova River, indigenous natives to Brazil once held funerals typical to their culture: ritual wailing, removal of visceral organs, and roasting the body to be eaten. After initially stumbling upon her book by chance, I grew more and more fascinated—perhaps I should say obsessed—by the works of Beth A. Conklin, a cultural and medical anthropologist who specializes in the ethnography of civilizations in lowland South America.

Conklin studied the Wari’ population, a group of natives living in seven villages buried deep within the Brazilian Amazon. She focused on their practice of mortuary cannibalism—at conventional funerals the deceased’s closest kin encouraged relatives and other attendants to eat little pieces of cooked human meat. ‘Endocannibalism’, or the consumption of members of the same family or community, was used as a method of mourning and honoring the dead. Upon reading Conklin’s introduction, I experienced an automatic gag reflex that lasted the span of two additional sentences.

Conklin went on to explain: “The Wari’ did not eat human flesh because they needed the protein. They were not trying to absorb the dead person’s life force, courage or other qualities. They were not acting out aggression, dominance or a desire to hold onto the deceased.” I realized that, to the Wari’, disappearing into the bodies of fellow tribes-members was seen as the norm, a tradition conducted out of respect for the dead and support for the living. The peaceful community stopped practicing cannibalism after they were contacted by outside government-sponsored expeditions, which shamed their cultural practices and coerced them to adapt to Western funerary practices.

Suddenly I was eight years old again, sitting in the pandemonium that was the cafeteria of Edward H. Bryan School. I wasn’t eating human flesh. For that matter, I wasn’t doing anything particularly conspicuous. Like the Wari’, I minded my own business and expected others to do the same. This expectation was broken as Shelly Liva and her entourage of equally well-groomed classmates trekked across the entire length of the tiled floor to make a small confined ring around my body.

“Aren’t you Korean?” I nodded.

I was not merely Korean; I was very Korean. I landed far closer to the left end of Asian to American spectrum, a distinction that meant Shelly Liva would become a defining character in the story of my life.

“My brother told me that means you eat dogs.” The girls circling me exchanged incredulous looks.

“No, not really,” I stammered. “Only once, but…” The girls knew I had lost the moment of that first concession. They didn’t bother to listen to my halfhearted attempts to explain myself out of the wrong. I didn’t know how I could be guiltless. I had eaten dog meat. I had eaten the flesh of man’s best friend. I felt Shelly’s silky blonde hair swish in my face as she and the others sauntered away.

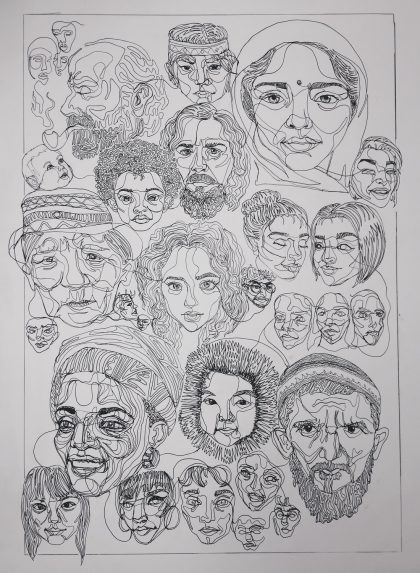

Grace Li is in Grade 10, Age 16, and attends Cranbrook Kingswood Upper School in Bloomfield Hills, MI

“The many different faces of my piece cover people of different religions, countries, ethnicities, ages, emotions, and creeds from all different walks of life. The drawing is made out of a single line, connecting and forming every single face. Each one of us comes from the same stuff, and it can sometimes be forgotten when looking at a person’s outwardly appearance. I hope this drawing conveys this certain message that we are all made of the same and are human in each and every respect. It can be so easy to judge someone by not only their skin color and religion, but in what they wear as well, and a huge disparity is brought to light as people begin to group and persecute others for these specific reasons. It’s dehumanizing in many respects. I’d like to drive that message home in this piece.”

Christina Lewis is in Grade 9, Age 15, and attends Charleston County School of the Arts in North Charleston, SC

“My poem relates to tolerance because it discusses race in America, which is unfortunately still a topic that is brushed under the rug and avoided…I think that it’s important for people of color’s experiences with prejudices to be validated. When a person of color’s story is acknowledged, the story has the opportunity to be shared with the general public to increase other’s awareness of their privilege, increasing tolerance.”

“To Look Like My Mother”

I remember your eyes like juniper

and mint leaves, the eyes you said held me

when I was just a twinkle

in your mind. Narrowing at the girl

who refused to sit on my bed

because I was too dark, and brown

paint stained. The first moment I remember

looking up at you,

your hair brushed like honey, curling

like the corks you collected from wine

bottles. Just long enough to shield my seven year old

face from the girls who whispered

behind their porcelain fingers, and your friends

who asked in the supermarket

if I came from a mission trip in Guatemala.

I looked up at your skin,

rosy from the camellias that blossomed under your cheeks.

Stretched over your bones and brushed the color

of rice my grandfather harvested with hands

like mine, fifteen thousand miles away from where we lived.

You were white in the places

it mattered. I wanted to take magic

marker to my irises and scribble ink that matched

pine needles and Atlantic sea foam, to twist

my hair like the bottle caps that swiveled onto and sealed

glass Coke bottles too expensive to buy

in India. I wanted to look like you and that girl, to snatch

the pale foundation from your bathroom counter

and rub it into the creases of my eyelids and the folds

of my knees that tanned too easily, never turning

cherry. I wanted to burn like you. Longed for the sun to

touch me, unafraid.

To learn more about Miri Ben-Ari and The Gedenk Movement, visit the following sites:

- Gedenk on the web: http://gedenkmovement.org

- Gedenk on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/gedenkmovement

- Gedenk on Twitter: https://twitter.com/GedenkMovement

- Miri Ben-Ari on the web: http://miribenari.com/

- Miri on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/miribenari

- Miri on Twitter: https://twitter.com/miribenari