On May 10, Philip Pearlstein joined the Alliance at Art & Writing @ Night and treated our guests to a retelling of one of his many remarkable stories; this one relating to his experience as a Scholastic Awards Alumnus during World War II. Today we’re happy to share it with you too! We hope you enjoy this very special piece of American and Scholastic Awards history.

A WAR AND TWO PAINTINGS

by Philip Pearlstein, May 2016

I was drafted into the U.S. Army in June 1943 upon completion of my freshman year in the art school of Carnegie Institute of Technology in my hometown of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I spent the next three years, two of them in Italy, as a GI. However, the fact that I had won two prizes in the National Scholastic High School Art Contest in 1941, while in the eleventh grade of high school, played a very significant part in my wartime experience.

Until I was 9 years old, I lived on Cherokee Street, at the very top of Pittsburgh’s Hill District. It was a large, racially mixed neighborhood, in which many of the white families were first-generation immigrants from various European countries. My mother was born in Lithuania and my father was born in Pittsburgh, shortly after his parents had arrived from Russia. After a brief time in Wheeling, West Virginia during the height of the Great Depression of the 1930s, my parents and I moved back to Pittsburgh. We moved into a small house on Murray Avenue near Greenfield Avenue that was also occupied by my father’s seven siblings and his mother. We made a family group of ten adults and me. As there were only three bedrooms in this small five-room house, I shared beds with my uncles, who rotated their sleeping quarters (someone was always sleeping on the living room sofa). It was in the living room, on a folding card table, that I began to make art, which subjected me to teasing from my uncles.

There were two highlights for me during my junior high and high school years. The first was the big flood of 1936, when our city was without electricity for a couple of weeks. We lived by candlelight, and no one was able to get to work. It seemed like an extended festive event. The second highlight came five years after the flood, when I won the National Scholastic High School Art Contest.

By then my parents and I were in our own apartment, after a few months of sharing an apartment with my Uncle Kiva, one of my mother’s three brothers, and his three children. My cousin Martin and I shared the convertible sofa bed in the living room. Martin, who was about 18 months older than me, was very bright and was into reading ‘serious’ books. I remember he shared John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath with me; it was the first ‘serious’ book I read. Previously I had surreptitiously read the illustrated comic books, like Doc Savage, and luridly illustrated magazines, such as True Detectives, that my uncles left lying around. This was when I was in the eleventh grade at Taylor Allderdice High School and hanging out in the after-school art club, which was led by a charismatic art teacher, Joseph Fitzpatrick. Mr. Fitzpatrick was tall, sophisticated and dapper, unlike anyone else in my world, and he had gathered about 15 talented students in his club.[i] At the end of each term, he directed us in creating the sets for the graduating class’s big theatrical production. One term there was an especially memorable Hollywood-style musical, directed by a young local dance teacher whose name was Gene Kelly. One day Mr. Fitzpatrick announced the names of those of us who had had work accepted into the National Scholastic High School Art Contest exhibition, and mine was among them. At the opening of the exhibition, I learned that I had won first prize for oil painting and first prize for watercolor painting.

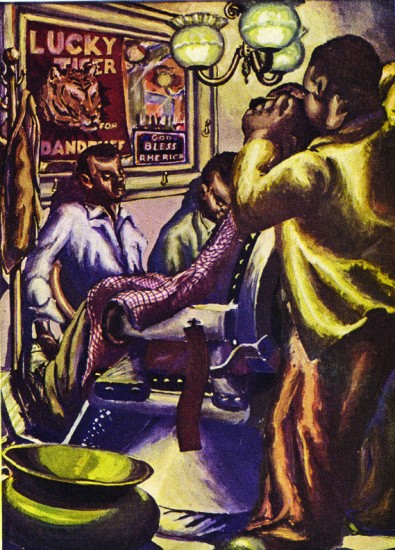

The exhibition of the works accepted by the jury that year, 1941, was held first at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. Then it was shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and it was written up in Life magazine. Suddenly, to quote Judy Garland in The Wizard of Oz, which was still in theaters at the time, I was “over the rainbow.” My two paintings were reproduced in full color in Life, the foremost national publication of the time, and I had my moment of revenge against my uncles, who had always made fun of my art-making. The June 16, 1941 issue of Life had two pages of color reproductions of a number of the works by the young artists. At that time, color reproductions were still relatively rare. My oil painting of a merry-go-round, the first-prize winner in oil paints, was given the entire top half of one page. My prizewinning gouache painting of an African American barbershop in the Hill District shared the lower half of the page with a painting of a railway scene by another young artist. My paintings related to the work of the American scene painter Reginald Marsh, who indeed was one of the jurors that year. The following year, I entered another oil painting of a scene at Kennywood amusement park and a colored-ink drawing of the facade of a local movie theater with a crowd gathered for the Saturday afternoon double feature. They were each awarded first prize in their categories, and I received a scholarship that paid my freshman year’s tuition at Carnegie Institute of Technology’s School of Fine Arts.

During my freshman year at Carnegie, most of the male student body took the introduction to military training (ROTC) instead of gym, and at the end of the school year, in June 1943, we all met at Fort Meade, Maryland. After being interviewed, all of my friends were assigned to the Signal Corps. On instinct, I had taken a copy of the June 16, 1941 issue of Life magazine with me, and I showed it to the officer who interviewed me. He seemed impressed, but I was assigned to the Infantry rather than the Signal Corps, packed into a very crowded train, and sent to Fort McClellan, Alabama, where four months of violent physical activity, training in a very hot, sun-blinding summer, transformed me from a pudgy, non-athletic person into a surprisingly muscular GI. Then abruptly one morning at roll call, I and several others were separated from those we had trained with, and sent by train to Camp Blanding, Florida. There I was assigned a place in a cabin with eight beds in Headquarters Company. I later heard from one of the men I had trained with at Fort McClellan that most of our fellow trainees had been shipped overseas as replacements for casualties in infantry landings at Anzio, Italy.

At Camp Blanding, I was assigned to the visual-aids shop, which was producing charts on infantry weapons for training purposes. The charts showed how particular weapons functioned, and how they were to be dismantled for cleaning and reassembled, etc. My commanding officers were Sgt. Lowery and Sgt. Chapman, who was second-in-command and oversaw the actual artwork. In civilian life, both men had been commercial artists on the West Coast, and they had recruited personnel who had also been commercial artists. I spent the next seven or eight months there learning how to use drafting implements, lettering, perspective, and design layout. We made our own silkscreens for printing the charts, and did the actual printing for editions of about sixty charts. We prepared the screens by smearing a gelatin mix on paper from which to cut the stencils. We did all the production work and all the cleaning up. In my spare time, I began making sketches and watercolor paintings of scenes of infantry training and everyday life in the camp.

I thought of myself then as a future illustrator. Having grown up in the 1930s during the Depression, the idea of being a fine artist seemed a financial impossibility. I did know one serious artist, Samuel Rosenberg, who was considered Pittsburgh’s foremost painter. He earned a living by teaching Saturday morning art classes for high-school kids at the Carnegie Museum, as well as adult art classes at a settlement house (although his son, whom I knew from those Saturday morning art classes, told me that he did sell paintings occasionally). I figured that if I survived the war, commercial illustration was what I would do. So I started making the drawings and watercolor paintings for my future portfolio. I experimented briefly with various styles: expressionistic, cubistic, and realistic. I thought of myself then as sophisticated, art-wise. However, my nice assignment in Florida ended when the Army decided to rotate us overseas, as replacements. Before departure, all of us from the Visual Aid shop were put into a three-month-long basic infantry training program at Camp Blanding. It was our second tour of basic training. Then we were all scattered overseas.

A month later, I was on a Liberty ship on my way to Italy. I sketched all the while on the boat. Our ship was part of a large convoy. Except for some Air Force men, nearly all of us were Infantry, with the rank of buck-corporal—two chevron stripes on our sleeves. It was said that there were five hundred of us corporals on board. The rumor was that we were to be casualty replacements at the Battle of Monte Cassino, which had been raging for months. However, the battle ended before we got there. We arrived in the bombed harbor of Naples in early fall, and were taken by truck to a tent camp in the Volturno River valley at the base of Monte Cassino. The location was said to be the property of Mussolini’s son-in-law. It rained endlessly, and the sloping ground was terribly muddy and treacherously slippery. We resumed training, running mock skirmishes in the foothills of the mountain, crashing through farms and small villages. All around the area there were temporary graves marked with wooden crosses or Stars of David, all painted white. We could also be tourists and ride in the open backs of trucks for evenings in Casserta or Naples. On one of my first weekends in Naples, I went to Pompeii on a tour run by the Red Cross. Another time I went to Capri. The great palace in Casserta was now the headquarters of the United States Fifth Army, and its spectacular gardens became an enormous parking lot for army vehicles. It was all very grim, except for these tourist experiences.

Our training there came to an abrupt end some days before Christmas. We packed, were trucked into Naples early in the morning, and waited all day on the platform of a bombed-out railway station to board a train to Rome. The trip on the train took all of that night, the following day and night, and another half-day. It took so long that until I returned to Italy on a Fulbright Fellowship in 1958, I had the impression that Rome was a great distance from Naples, rather than a short three-hour trip. When we arrived at the Rome railway station we wandered around like tourists, as it was the first really large-scale modernist building any of us had ever seen, until we were picked up by trucks to spend the night in a warehouse. Then the next day we were trucked into the countryside to modernist-looking brick barracks. Either that night or the next was Christmas Eve. I remember going into Rome by truck and going to the ceremony at Saint Peter’s, where there was an enormous crowd mostly of soldiers from several different national armies.

Suddenly, those of us who held the rank of corporal (which I held for my work in the visual–aids shop in Florida) were told we were to train soldiers who had been kitchen cooks, truck drivers and office workers in the North African and Sicilian campaigns and the retaking of the boot of Italy of the previous three years. Their jobs were now “surplus.” They were to be retrained as basic infantry soldiers, regardless of rank, for the Allied Forces’ big offensive push across the Apennine Mountains between the cities of Florence and Bologna, where the German army had retrenched after its withdrawal from Rome. We were interviewed again. I still had the June 16, 1941 copy of Life magazine with me. When my interviewer realized that my given rank of buck-corporal was for artwork, not fieldwork, he assigned me to take the basic infantry training again rather than teach it.

The training program took place in the area that Mussolini had begun to build for his 1942 World’s Fair, which was meant to celebrate the 20th anniversary of his fascist rule. These grandiose but unfinished buildings were all occupied by units of soldiers of different nations: Britain, France and America. The British troops were mostly Indians from India, and they were housed in what is now referred to as the “modern St. Peters.” The Americans were in the section now called Città Militare, which is still used by the Italian army. The neighborhood where it is located is called Cecchignola. In the late 1970s, when I visited Rome again with my family, there was a well known outdoor barbeque-chicken restaurant right at the entrance to the military city. On my most recent visit, I saw that an enormous apartment complex stands on that site now. The whole area is now a section of Rome called EUR, with many of the buildings constructed for the World’s Fair now housing government bureaus in handsome Art Deco style. In our days of training, we often marched past ancient Roman ruins along the Via Appia Antica, and several times passed the entrance to the Ardeatine Caves, where the German army had massacred hundreds of civilians. I remember once going into the caves during the days before we left Rome and seeing dozens and dozens of portrait photographs of the victims, illuminated by commemorative candles.

My comrades in this third round of basic infantry training were an older, more sophisticated group of men with varied cultural backgrounds, many of who had been transferred from clerical positions. One man I became friendly with had been involved in theatrical stage design. Another had trained to be a classical singer. His name was Herbert Levine. We met again when he looked me up in New York after reading a review of one of my early exhibitions, and we went to dinner a couple of times. We met again around 1985, when I gave a talk at the Brooklyn Museum and he was in the audience. During our training program, he and I, along with a few others, went to the opera in Rome one night a week for a couple of months. We rode on trucks from our compound through the countryside to the city. The city of Rome then really only extended to St. Paul’s Basilica Outside the Walls. Around 10 or 11 o’clock, the trucks returned to the pick-up point in the city, which was the large square in front of the round tomb of the Emperor Augustus.

This group of fellow trainees had almost all been to college. The army during World War II was a truly democratic experience, but aside from the artists in the visual-aids shop at Camp Blanding, it was unusual to meet men who had been to college. In my first basic infantry training experience, those with a college background were looked on with suspicion. Now I enjoyed being with this group of literate older men. The same group of five or six that went to the opera on Wednesday evenings also went to the museums that were open and to the famous churches to see the paintings and sculptures on weekends. I was then 19 years old; the others were in their late twenties or early thirties, and a couple of them were married with children.

One day in camp I ran into one of my former colleagues from the visual-aids shop in Florida, Ray Neiman from St. Louis. He had managed to be assigned to painting signs, and had set up a shop at the back of the motor pool. The Army always needed signs. As the training period neared its end, Ray made the effort to have me assigned to his shop as his assistant. All the while I continued to make drawings and sent them home to my parents. Our platoon leader, who had to censor our mail, liked the drawings. One evening he visited me and I showed him the reproductions of my paintings in Life magazine. He was Sgt. Gluck, from Brooklyn. He facilitated my transfer to Headquarters Company, and to the sign shop, while my fellow trainees went into combat over the Apennine Mountains, across the Po Valley and into the Italian Alps.

On May 14, 1945, just before my 20th birthday, I was sightseeing in Rome, the sole visitor in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli (St. Peter in Chains), studying Michelangelo’s statue of Moses and puzzling over a story, in Italian, on the wall that explained why the surrounding structure was a reduction from a vast planned tomb for a pope, when a youngish priest walked over to me and in perfect Americanese said that the war in Europe had just been declared ended. I felt a wave of relief—and then surprise, as I had never expected to see the end of the war. For two years I had been in almost constant training as an infantry foot soldier, in infantry casualty-replacement camps, but miraculously had never been sent into actual combat. The priest asked me where I was from in America, and when I said Pittsburgh, PA, he threw up his hands and said he had spent several years serving at a cathedral in Pittsburgh, in the neighborhood of East Liberty, and he wished me a swift return to Pittsburgh.

However, the war wasn’t over yet for me. Ray and I continued to paint signs in a small brick building at the far edge of the motor pool for a couple of months. Attached to the back wall of our shop, a group of seven or eight young boys had improvised tent housing for themselves, hidden from the U.S. army. They had a leader, who seemed to be about 15 years old. They were self-sufficient, didn’t steal from us, and we made no contact. Ray and I only observed them through a back window. Suddenly a couple of us from Headquarters Company were given a ‘rest tour’—a week in Venice. We rode in the back of a truck from Rome to Florence, and to reach Bologna we traveled across the Apennine Mountains on a road that was churned up from the months of artillery pounding. On arriving in Bologna, I had a tooth pulled out by a medic. (That tooth was not replaced until sixty years later and the empty space was a constant reminder of my army experience.) Our truck ride continued the next day in the Po Valley through total devastation. The roads and bridges were all makeshift. As we rode through towns, the people held their hands out begging for anything.

It was wondrous to arrive at intact Venice to see electric lights in the evening. I realized then that I had seen only kerosene light since my arrival in Italy a year earlier. Another GI from Headquarters and I were assigned to a room in a third-rate hotel on the Lido. We became friendly enough, and we spent the week touring the city together. There was a great exhibition of works of art that had been safely stored away during the war and were now hung in the Correr Museum, which occupied the top floor of the interconnected Renaissance buildings that surround three sides of the Piazza San Marco. The British army had a unit of art experts who arranged many similar exhibitions throughout Italy as the big cities were liberated from the Germans. They published catalogs of the exhibitions in English, and I still have several of them.

Sometime after this trip, Ray and I were assigned to an engineering company that moved from Rome to a small picturesque seaside town at the mouth of the Arno River, called Marina di Pisa. It was not far from Pisa, and just north of Livorno. Our Company’s assignment was to maintain the highways between Rome and Florence. German prisoners of war were the workers, our men the supervisors. Ray and I painted whatever signs were needed. The men we were now with were quite different from those I had been with in Rome. There were about twenty-five of us in total, and except for Ray and me, they had all been construction workers as civilians. Three or four had been to college. Several were from Italian-speaking families. We were assigned to a private house with many rooms and a large yard with several small buildings. This complex became industrial looking very quickly. We were living independently of other army units, and our three officers had their own house. So life in our house quickly became a constant party in the evenings—cases of beer and wine were consumed, and jazz and popular swing-time dance music constantly blared from our small radio. Soon a number of the available local young ladies from the town moved in. Many of our men were in their late twenties or thirties and married; several had families. They were enjoying a last fling before returning to the U.S. In the bedroom to which Ray and I were assigned, I immediately set about making finished versions of some of my drawings and watercolors for my future portfolio. As I was the youngest of the group, and probably thought of as eccentric because I was serious about art, I was tolerated with humor by these older, rougher men.

On a few days each week one of our trucks went to Florence, to the Fifth Army’s headquarters, which were then located in the Pitti Palace, to take care of laundry service and mail. I made a number of such trips and spent all the time I could visiting churches and museums to study the art. The Pitti Palace itself was full of ancient and Renaissance art. In the courtyard where our truck parked, the original Ghiberti and Donatello bronze doors of the Baptistery were leaning uncovered against a wall. They were black then, before post-war cleaning revealed the bronze and gold. A five-minute walk from the Pitti Palace took me to the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, where I would give the attending monk in the dark church a few cigarettes and he would allow me to visit the Brancacci Chapel with the Masaccio frescoes. The lower level of the chapel was filled with sandbags and scaffolding. Because I was the only visitor there, I climbed up the sandbags, stood on the scaffolding and studied the details of the paintings, especially those of The Tribute Money. I memorized each of the faces, hands and feet in the paintings. The only light came from the open front door of the church. (A couple of years ago, I visited the chapel after the cleaning and restoration of the church and frescoes, and found it to be quite a different experience. After standing in a long line of tourists to have my turn in the chapel, I experienced a letdown. This new experience of brilliantly lit frescoes, while exciting, had lost the magic of my long-ago experience).

Because we were a small unit, we were able to take ‘rest tours’ frequently. I went to Milan and Genoa, and twice to Switzerland—once in the fall, and again for winter sports. In every city in Italy, there were wonderful art exhibitions set up by the British army’s art specialists. For me the trips were enlightening art experiences.

Meanwhile, the situation in our unit became rather surreal. Separated from the rest of the Army, it seemed almost as if we had been forgotten. Our house grew filthy; the partying became a twenty-four hour experience and, as the men were being sent home according to time spent in the Army, our numbers kept decreasing. Ray left, and I became the only sign painter. As the months passed, the supply of white paint for the signs disappeared, as did all electrical supplies. Most of our men had become involved in the black market. A couple of our officers who had families in Italy were buying local houses, and refurbishing them with the Army materials, using the labor of the German prisoners of war. There were miles of rows of all sorts of Allied Army vehicles, and huge wooden crates filled with supplies of all sorts piled in neat rectangles in fields along the highway, all useable by civilians. Shipping all this military surplus back to the United States would have been too expensive. In fact, Senator Fulbright’s scholarship program of sending students and scholars to study in Europe was partly funded by the controlled legal sales of these materials. Everything was for sale, even our latrine waste. Men in charge of vacuuming the army latrines in the area were selling the human waste to the local farmers for fertilizer, spraying it out onto the fields. One of our officers was found murdered in his jeep in Lucca, a victim in the black-market war that came to a head in the following months. The black market thrived.

I was the youngest, the naive one of the group. Several of the older men would trust me with their money when they went off base. However, the incident that brought our unit back to the attention of the area Army authorities was the suicide of one of our men. I was on office duty that night and had to call the local Army headquarters in Livorno; and, as most of the men were away for the weekend, I and another man collected all the guns we could find on the premises to avoid penalties. In the dead man’s room, dogs were licking up his blood from the floor.

Within two weeks we were transferred to Livorno (called Leghorn by the Americans), to quarters adjacent to a large German POW camp, which was guarded by Japanese-American GIs. I was in charge of a group of five German POWs who built and painted the wooden signs. The Italian roads and highways then were primitive, narrow, twisting, two-lane roads with hairpin turns—and lots of bomb damage. A truck ride was hair-raising. Our signs said things like “blow your horn,” “go slow,” and “stop.” The signs were almost always black block lettering against a white or yellow background. We had our own large, comfortable shop, and I spent my days in isolation with the Germans, a couple of whom had been commercial artists as civilians; the others were craftsmen. One of them had been the chief calligrapher for the German movie studio UFA. He said that he had done the subtitles for many movies, including The Blue Angel starring Marlene Dietrich, which was a fairly recent movie back then (though I had not seen it). We both spoke enough broken Italian to communicate, and he gave me lessons in script calligraphy.

Our community was now more complex, as many of the German prisoners, especially those of higher rank, went around dressed in the same GI uniforms as the Americans, without POW markings. They had been stationed in this area long before us, and they knew the local women that were invited regularly after dinner to our mess hall, which turned into a nightclub every evening. The German upper-rank prisoners mingled freely in the drinking, carousing and dancing, while several of the German POWs who were musicians performed jazz. It was a scene from a Fassbender movie.

I did not have enough ‘points’ to be sent home; and, as the older men left, I became one of the seniors of the organization, regarded with awe by the new replacements from the States because I had been there while the fighting was still going on. It didn’t matter to them that I had never been in combat myself. Finally, one day in April, I was given my orders to return to the States. My group of German workers in the sign shop gave me impressive farewell gifts: two Bavarian-style picture frames decorated with ivy leaves and acorns, carved by one of them from mahogany wood, as well as two small wooden trunks they had made. I returned to Naples by train, and again boarded a Liberty troop ship. After many days of storms at sea, with the ship rocking violently, and intense and messy seasickness experienced by almost everyone, I arrived at a camp in New York and was processed for discharge from the Army. One month shy of three years in the Army, I was home to celebrate my 21st birthday. My first project at home was to paint portraits of my mother and father to fit the two carved frames.

I still have the original copy of Life magazine, the Windsor and Newton metal watercolor box I brought overseas with me, and a set of drafting instruments I bought while in Switzerland. I also brought home a camera called a Kiwi, which had a flexible bellows, but after a year or so back in Pittsburgh I traded it in for a new camera because it was an old film-pack camera that didn’t use film rolls. Most of the pictures that I took, or that were taken of me, in Italy were simply typical tourist-type photos of me or a friend in front of some monument. Unfortunately, the most interesting photo, which was of me standing on a pile of rubble in front of Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper, is out of focus forever. I am standing on top of a mountain of sandbags at the base of a freestanding wall, like a billboard, with just a narrow shed roof along the top of the wall to protect Leonardo’s painting from rain. Miraculously, only that single wall of the monastery was spared in the bombing. The set of drafting instruments from Switzerland (ruling pens, compasses, and a device called a proportional divider) were counterparts of the ones I had used in the visual-aids shop in Florida, and these became important in the next phase of my life.

On my first visit back to the art department at Carnegie Institute of Technology, while describing my experiences to former classmates and faculty members, I was hired on the spot by Professor Robert Lepper. He had just started a job outside of school, designing a series of catalogs of products for architectural use for ALCOA, the Aluminum Company of America. My art experience in the Army qualified me to be one of his assistants on the production work for the printing press. (Later, in New York, I found that such work was regarded as the lowest level in the field and was referred to as “doing paste-ups”). I worked with Professor Lepper on the catalogs for the next three years. On his recommendation I became the art director of the engineering school magazine, The Carnegie Technical. This was excellent preparation for life as a graphic designer. On graduation from Carnegie, after three years back in Pittsburgh, I went off to New York to become part of the commercial art world.

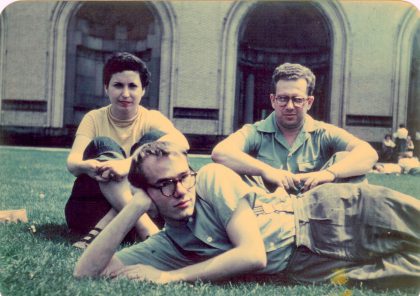

I had a companion on my move to New York: Andy Warhola (he later dropped the final ‘a’). He was several years younger than I was, but we had become close friends during our sophomore year. I had recognized him as extremely talented, as did most of our classmates, and (as someone many years later pointed out) he was perhaps attracted to me as I had been briefly famous because of the Life magazine article. I often helped him by explaining the more complex assignments given in our design class by Professor Lepper. He occasionally worked on assignments with me in the studio I had fixed up in the cellar of my parent’s small house. Andy’s two brothers, who were much older than he was, knew my father, as they worked together in the wholesale-produce market of Pittsburgh. Andy’s father had died when Andy was very young, and had left an insurance policy that paid for Andy’s college tuition. Both our families were lower middle class, still stuck in the experience of the Great Depression of the nineteen thirties, with little knowledge of art. (My mother once expressed surprise that her only child became an artist. When I asked her what she thought I might have been, she said after a pause, “Maybe a buyer in a department store.”) Andy’s very protective brothers agreed to let him go to New York if he could live with me, as I was older and, presumably, wiser. We did live together for about nine months, the first two months in a sublet cold-water flat. Then we moved into one large room that was part of a modern-dance studio, which we sublet from the modern dancer Franziska Boas, the daughter of the famous anthropologist Franz Boas, whose old notebooks and collection of books were in a bookcase in our room.

During our last year at Carnegie, we had both prepared portfolios of work to present to the New York art directors of advertising agencies, magazines, and book publishers. I put away my wartime sketches and watercolors as belonging to the past, and instead developed a new group of works. I believed that there was a future for visual training aides in the field of education. For my portfolio I designed a “dummy” of a booklet illustrating the background for some of the arguments behind ideas that went into the writing of the Constitution of the United States, and a couple of large charts diagramming the ideas that formed the Electoral College. I envisioned the latter as theatrical stagings.[ii] However, in the summer of 1949, the art directors in New York looked through my portfolio briefly, saw that the subject of the charts was the United States Constitution, closed the portfolio and said, “What are you, a Communist?” and that would end the interviews.

Eventually I did get a job. Through the recommendation of another friend from Carnegie, George Klauber, I was hired by the graphic designer Ladislav Sutnar, who had been a pioneer of the field in Europe before World War II. He had designed the Czech Pavilion for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, and when Germany took over Czechoslovakia, Mr. Sutnar was sent to New York to sell off the materials for the pavilion, which had not yet been erected. He stayed on in New York and became the design coordinator for Sweets’ annual publication of catalogs of materials for the architectural and building trades. Mr. Sutnar did not like the work in my portfolio, but said that he respected the ambition. I worked for him for the next seven years, sometimes full-time, sometimes part-time, paid an hourly rate. The set of drafting instruments I had bought in Switzerland served me well during those years. We worked on a variety of catalogs and projects, but mostly for American Standard sanitary plumbing. Mr. Sutnar also told me that I, like most American art students, was badly educated. He encouraged me to study art history using the time I had left on the GI Bill, and work for him part-time. I was accepted at New York University Institute of Fine Arts, an educational experience for which I was ill equipped, but I had been accepted based on the high grades I had earned for studio courses at Carnegie Tech. I married my wife, Dorothy, a few weeks before classes started in September 1950.

It was only because I was used to Mr. Sutnar’s heavily-accented English that I survived the lectures given by the distinguished group of European-refugee art historians who comprised most of the faculty at the Institute then. Seminars were a flow of English, German and French. I almost drowned until I started to make visual charts of the material in the courses. Making the charts proved a good way of reviewing the material, and I memorized the charts the night before an exam. My grades went from Cs to As. I tried to study the German language with the wife of one of the professors, but the books we used were printed in the old gothic-type style, and I was thrown. She finally asked me “to please to stop studying German with me.” I did begin to learn to read and translate French, tutored by a fellow student, Lucia Sherwin. As the subject for my MA thesis, I chose the Dada work of Francis Picabia, which had to include that of his friend, Marcel Duchamp, largely because his paintings of the Dada era of World War I were based on the kind of technical illustrations I had been working on in Mr. Sutnar’s office. Through a fellow student at the Institute, I heard about, and then attended regularly, panel discussions held every Friday night by the contemporary artists called Abstract Expressionists and their circle of writer friends. The paintings I was then making, working late at night, became heavily influenced by their work.

Picabia died just as I had gathered most of the material, most of which I had had to translate from French. And, as the leading expert on his work at the moment, I was asked to write an article for Arts magazine, edited by Hilton Kramer. The article’s title, The Secret Language of Picabia, turned out to be the first major article in English on his work for a couple of generations. It appeared in January 1956. One year earlier, in January 1955, my first solo exhibition was held in an artists’ co-operative gallery, The Tanager, on Tenth Street. The paintings I exhibited were an amalgamation of ideas from medieval Chinese landscape painting, Cezanne, and Abstract Expressionism. On being notified that I had been awarded a Master of Arts degree in June 1955, I realized I wouldn’t continue on the path of becoming an art historian—that I really wanted to concentrate on painting. Nor did I see a future for myself in graphic design. Although, I continued to work for Mr. Sutnar until sometime in the late summer of 1957, when I left his employ and went to work for Life magazine, doing layouts of articles, which was far less demanding and gave me much more time for painting.

At Life I did not mention to anyone the fact that 16 years earlier I had been written up in the magazine as a promising young artist, because I felt embarrassed that after all this time I had not gone very far in my painting career. My son, William, was born about two months after I went to work there, and soon after that I received notice that I had been awarded a Fulbright Fellowship to go back to Italy as a painting student the next academic year. So in September of 1958 I took a leave of absence from Time, Inc. I brought in my old copy of the June 16, 1941 issue of Life and showed it around during my last week. My fellow layout artists were thrilled, as if the issue had just come out. They presented me with a new camera and several rolls of film for my year away. While I was still in Italy, I was hired to teach courses in the first-year program at Pratt Institute, and I never returned to Life magazine.

During my year as a Fulbright Fellow in Rome I made many realistic wash drawings of the ancient ruins in the Forum, which I then saw as a metaphor for the waste of war. The paintings I did in the evenings, working from the drawings, were still highly influenced by the Abstract Expressionists at first, but gradually approached Realism during the year. On my return to New York I continued the series of ruin paintings, started my teaching career, and moved wholeheartedly into Realism as my painting style.

In the late 1970s, Scholastic Magazine celebrated its fiftieth anniversary and held a luncheon attended by as many of the former high school art-contest winners as they could locate. The major speech was given by the famous sculptor and furniture designer Henry Bertoia, who had been the very first winner. I was presented with my painting of the merry-go-round, which the magazine’s publisher had kept all those years, following the rule that the prizewinning pieces would be kept by those who put up the money for the prizes. Scholastic Magazine had awarded me two first prizes of twenty-five dollars each. The water-based poster-paint painting of the African-American barbershop had been lost. The oil painting was given back to me unframed. I felt disoriented; it was as if one of my three children had done it, and I should have been proud of my child, but I couldn’t remember which one was the artist. Weeks later I had it framed and hung it in our living room. The artist Raphael Soyer, whom I became friends with after he bought a drawing of mine, saw it on a visit and was puzzled. He assumed it was a painting from the 1930s that I found, and he was trying to guess which artist of the time had done it. The painting is so much of its time, and I was so lucky to have painted it, and lucky that it won the prize, and lucky that Life magazine had written up the exhibition. All of this gave me the equivalent of a passport that had allowed me to pass safely through World War II, and to have a career as an artist.

[i] Several members of Joseph Fitzpatrick’s high-school art club went on to have careers in art, including Martin Friedman, who for many years was head of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis; Irwin Kalla, who became a major designer of household goods; and Lee Goldman, who was head of one of the design units of Corning Steuben Glass and who later became head of the art department at Carnegie Tech. Some of the other members went into advertising. During the war years, Mr. Fitzpatrick was transferred to another school, where he taught Andy Warhol. When Mr. Fitzpatrick died, his obituary appeared on the front page of The New York Times, with Andy Warhol, myself and several other artists listed as his students.

[ii] I was always interested in theater design, and had gone to see plays that came to Pittsburgh during my high school years—tickets were inexpensive—and had seen, among other productions, Orson Well’s Julius Caesar and Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. During that time I built a miniature theater stage, with lighting, complex stage sets and miniature costumed marionettes, that fit on top of a folding bridge table. My high school friend Martin Friedman sometimes joined me in this activity; in fact, it was an idea we had for a play that led to me doing the painting of the merry-go-round. We had been walking through Pittsburgh’s Schenley Park, and passed the merry-go-round that was there then. It was darkened, and we began to make up a play about a murder on it. When I did the painting, it was as a sketch for a three-dimensional set I was going to make. Of course, after the painting was awarded the Scholastic Magazine prize, painting won out over theater design. The stage and all the sets and marionettes were tossed out when I moved to New York.