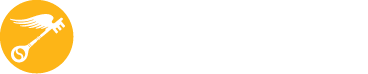

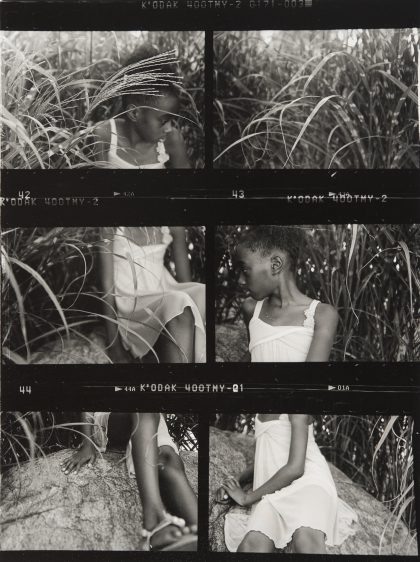

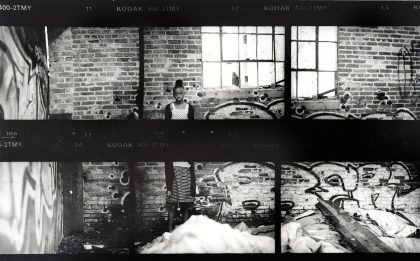

Nostalgia is a powerful device in the art and writing of Nyanna Johnson and Alex Zhang. Both students received Gold Medals for their portfolios which focused on revisiting the past and evoking emotions with their words and images. Nyanna and Alex take us back in time to give new meaning to the present in this next installment of Eyes on the Prize.

Nyanna Johnson is from Dayton, Ohio and attends Stivers School for the Arts.

“My photography tells a story. Through my series of work, you take a fictional journey with a young dancer, who returns home to see her house burned down. The photos provoke emotion through contrast and the separation of the pictures. You are able to travel through the whole scene of the house with the composite layout. The lighting creates shadows that reveal the girl emotion of sadness as she revisits each room.

“There has been debate on whether photography is a true art form, and I believe it is. Although it appears we are only regurgitating images we see before our eyes, it is actually much more than that. We artfully and skillfully create images, through cropping, lighting, and focus, to make mundane things you may pass every day, meaningful. While it may sound simple, it is very difficult and takes a lot of practice, but the outcome is something astonishing.”

Alex Zhang is from Exeter, New Hampshire and attends Phillips Exeter Academy.

“Writing provides me with a sense of understanding, it allows me to reflect and acknowledge where I am now and where I want to be. Writing is my sanctuary. When I read my pieces, I return to those days spent in the schoolyard and with my father, a time when things were both difficult and easy. I recognize the many fragments of my life that piece together my identity. My portfolio is a reflection of me.”

“Father Tea”

Personal Essay & Memoir by Alex Zhang, Grade 12, Age 18, Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, NH

Black

My father drinks only darkness.

I am five. On winter nights, we sit together in the screened porch and watch the stars with mugs clenched between palms. His breath forces steam from the cup’s edge and into the bitter air. I bring my face close to my tea and inhale the scent—sharp and acrid. Beside me, I hear my father slug gulp after gulp; I fence the full cup between my fingers until it’s cold.

Green

I remember the sensation of coarse leaves splintering against my tongue.

On my first trip to China at the age of six, we attend an all-family dinner; tea arrives with the meal in place of water. Thirsty, I tug my mother’s gray sweater and gesture to my throat. She reaches across the table and grasps the handle of the communal pot. I peer through the open lid, asking where the teabags are. She chuckles, lifts my porcelain cup, and fills it to the brim. The leaves float like miniature boats in a steaming pool of algae.

Red

By the time I am eight, I have developed an addiction for bing hong cha, which translates to “iced red tea.” It’s the Lipton of China, so drenched in sugar that my mouth floods with cavities by the time I am nine. On the way back from the dentist, my father yells at me in Chinese: “How are you this stupid? You only have one set of teeth.”

The entire time, his tea-stained incisors—off yellow—dip with each word.

Oolong

People might think this is “authentic” tea, but it’s only something you sip in the Japanese section of Epcot at Disney World. My family visits the theme park to celebrate my tenth birthday. The trip ends early. We leave after my father argues with the waiter and demands we go to another restaurant, one with real tea—Chinese tea. The lights of the park vanish in the rearview mirror while tears run down my cheeks. My mother holds my hand, softly sings Happy Birthday. My father frowns into the windshield at the black pavement rushing past. He turns up the radio. I taste only salt.

White

It might as well be water; you might as well not drink tea at all.

Yellow

My grandfather consumes only yellow tea. We visit him in Shanghai when I’m thirteen; I recall my parents arguing the night before.

“You have to see him, he’s your father,” my mother reasons.

“He was no father to me.” I hear the slam of his fist as it lands firm on a tabletop.

The next day, we lurch through traffic until we reach my grandfather’s yellowing stone apartment. Inside, I sit on the living room carpet and play with a blue toy truck he gives me. In the kitchen, a kettle screams and my father rushes to turn the burner down. He drops the pot; I hear the crash of the metal against tile. “How are you still this stupid?” my grandfather hollers in Chinese from his rocking chair. My father mutters as he wipes with towels that stain piss-yellow. We don’t visit again until years later.

Mint

I develop an obsession for mint tea in high school after the purchase of a shiny, chrome Keurig.

In October, my father calls me to complain about my Amazon purchases. “Why the hell would you order mint tea? I don’t understand.” I struggle to comprehend his rushed Chinese. “Remember your roots,” he spits before hanging up.

The next week, an aged gray teakettle arrives along with three packs of foreign green leaves wrapped in Mandarin labels I cannot read.

Jasmine

Every day, I visit a local coffee shop and order a twelve-ounce cup of Jasmine tea. The smiling barista hands me a delicate white timer set for three minutes, though most days I leave the bag steeped long after the beeps, the way father likes it. I will never tell him though.

Lavender

My mother is a fan of delicate teas, a category that encompasses everything bearing the names of flowers.

On her birthday in March, I boil a fresh pot of Lavender tea. But walking to the dining room table, my feet stumble and the clay pot shatters on the wooden floor. The liquid seeps into the cracks and the room fills with the scent of summer. My father stomps across the room; he chucks paper towels at me, yells into my ear. My mother pulls him away gently by the arm and I sop up the mess in silence.

Pu’er

Real black tea—it’s fermented, bitter, aged, and the color of winter midnights.

I am seventeen. Some breaks, I return home to find my father has unearthed the faded pu’er tin from the upper cabinets and left it open on the counter. In the confines of the screened porch, he peers out into the darkness with a scalding cup firm in his hand. There is no son at his side. I glance back one last time before proceeding up the stairs to my mother calling welcome.

Sun

Sometimes I imagine my relationship with my father as a cup of tea—a cup of sun tea. It’s prepared by steeping tea leaves in a jar of tap water and leaving the mixture to bask in the sun. In most cases, however, the rays are not enough to kill the bacteria. The concoction festers until no longer identifiable—the surface rankled with off-white globs, the color decayed to septic brown. This is our father-son drink. I don’t want to think about the taste.

I am trying to find the words to say he was too bitter.

To see more Gold Medal Portfolio recipients, past and present, visit our Eyes on the Prize series.