What does it mean to be an “emerging” young artist or writer? Finding your voice and articulating your vision requires that you possess a point of view, know who you are, and are ready to make that statement. As this 2013 Scholastic Awards’ Gold Medal-winning portfolio pair prepares to leave the creative chrysalis, they use humor to explore who they are and how they can stand out.

The Culture of Secrets, an Alphabet

Anthony

From the Latin Antonius. I never believe Papa Nicki, my great-grandfather, when he tells me that my name means “worthy of praise.” I tell him too many people are named Anthony for it to mean anything special, and yet, he has a way of saying the word that’s different than when he calls any of the other Anthonys in our family by their name. This is especially true now that we both knew that he’s dying.

“Anthony,” he says to me from his hospital bed. My great-grandmother cries in the corner, but only he and I exist in that cramped room. He grabs a limp hold of my arm and tells me to have many children—preferably sons. My family has told me this all my life. “We need you to continue the family line,” Papa Nicki says, “to not let it wither away in this country.” I only bring myself to tell him I love him.

Biscotti

An Italian dessert, also what I think of when I think of marriage. Grandma Della puts two of her homemade chocolate biscotti on a plate for me alongside a glass of milk. My grandparents’ house is quiet enough for me to hear the rigid cookie crunch in my mouth as I chew. I eat my biscotti with my grandfather as Grandma Della cleans the kitchen. He tells her what she could have done to make dinner better and asks her to pour him more coffee. When I fall in love, this isn’t what I want it to be like.

Connor

First boyfriend. He has rich, Charlestonian blood in his veins and so I make room for one more in the closet. “Please, my family will love us both even more when we come out,” I say. He asks me when I think that’s going to happen. “Soon,” I say, “real soon.”

Della

Grandma Della tells me that the Vietnam War hadn’t even lasted a week before she and my grandfather rushed to a courthouse somewhere in Brooklyn to get their marriage license. She now loves him so much that she cooks perfect meals for him, does his laundry with precision, and cleans his house with the knowledge that he won’t always say thank you.

English

One day while we shop through the cleaning supplies aisle of Publix, my sister asks our parents why they’ve never taught us to speak Italian. They explain that they never learned it themselves. Our grandparents can’t speak it, either. Their parents could, but only because they had to serve as translators for their parents, the first of our family in America. I realize how trapped I feel in three generations of English.

Soon after, I purchase a book of Italian Grammar and begin to flip through the pages. A boy I’ve had a crush on since grade school sees me conjugate the verb “negare” and asks me why I feel I have to teach myself Italian. I don’t answer. They he asks me what “negare” means and I say, “To deny.”

Family

I have it all figured out once. I will marry my preschool sweetheart, Catalina Bernadini. We will have ten children, all sons, and name them all Anthony. That would please Papa Nicki. After my parents pull me out of Catholic school and dump me into a public school, though, plans change. Thank God.

Gay (An obvious choice, but hear me out.)

“So at that art school you’re going to,” my grandfather says over Sunday dinner one summer afternoon, “what are you going to do if, you know, one of those gay guys comes up and asks to see your salsice?” Because clearly gay men are only after the salsice.

I tell my grandfather that I’ll say, “Sorry—not interested,” and he laughs.

“Hey that’s my guy,” my grandfather says, “My guy’s not a faggot.” I don’t sleep that night.

H

H is silent in Italian.

Read the rest of The Culture of Secrets, an Alphabet here.

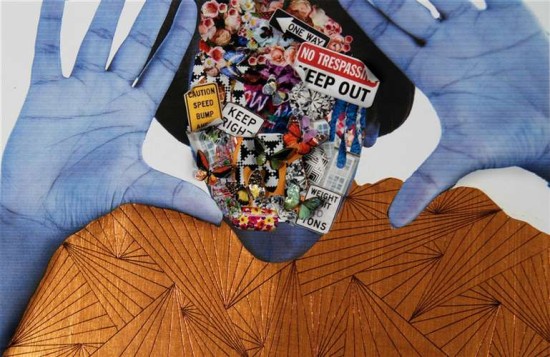

We wondered why Katiuscia’s work, like the collage shown above, shows partially-obscured faces and bodies. She explains: “My figures are never fully depicted but are masked, representing my struggle yet ambition to emerge as a young artist living in this world. As a young artist, I am overwhelmed by all of the original thinking and excessive talent. One may take this as a positive, but I also find it to be a challenge.

“This makes me wonder, well how do I stand out in a world where talent, vision, and originality is everywhere? I take this challenge and use it as a source of inspiration for my art.”

Anthony’s work also addresses different aspects of his identity: as a son, as as an American, as a gay man, and more. As the only male son in his generation, he feels the pressure, and the inevitability of disappointing his family in extending it: “I am the end of the aforementioned bloodline,” in a world far different than his immigrant grandfather. But he takes solace (and sees humor) in the realization that writing helps him express his feelings. He says about The Culture of Secrets, an Alphabet:

“The piece is significant to me because I wrote it in the midst of coming to terms with my homosexuality… It serves as a reminder of how writing has been the greatest way for me to make sense of the only world that I never had a say in creating.”

See more of Katiuscia’s art and read more of Anthony’s writing.