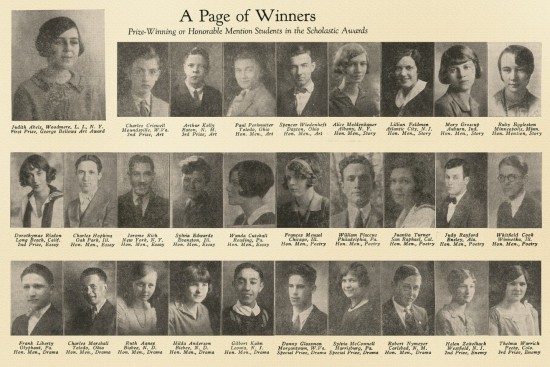

While this year’s Gold and Silver Medals (and Keys!) are still shiny, and the artists and writers who earned them float on cloud nine, we can be sure of one enduring fact: the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards have delivered this kind of validation to creative teens for 90 amazing years! To celebrate this milestone, we dug into our vast archives and turned to esteemed colleague Bryan Doerries to tell the story that started in 1923 with just 7 submissions and is now the largest, most prestigious awards program in the U.S. Here’s a sneak peek at The Great Encouragement with Bryan as your guide!

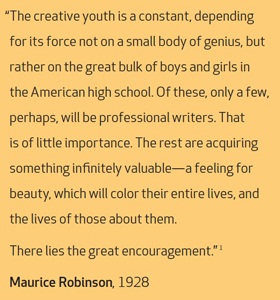

How did you come up with the title?

While pouring over anthologies of past Scholastic Award-winning student writing from the 1920s and 30s, I stumbled across an introductory essay written in 1928 by Maurice Robinson, the founder of Scholastic and The Awards. In it, Robinson conveyed the spirit of the program, distilling it to its very essence in just a few words:

In Robinson’s estimation, The Awards were unapologetically a contest, but the ultimate prize wasn’t cash, or scholarships, being published, or the promise of professional success, it was “a sense sublime of something far more deeply interfused,” as Wordsworth writes, which can only be acquired through the act of creation. By challenging young people to cultivate “a feeling for beauty,” The Awards have rewarded every student who has risen to the challenge and taken the risk of submitting his or her work to the program.

What did researching about the history of the Scholastic Awards reveal about the history of education in America?

I discovered that in the 1920s, right around the time The Awards came into existence, there was a burgeoning movement within American high school education away from the didactic and dictatorial approach of 19th Century toward a more creative and collaborative approach to learning. The word “creative writing” itself was coined by a progressive educator and author named Hughes Mearns, who introduced the writing of poetry and fiction to the core curriculum at Lincoln High School in New York City. In 1925, he wrote a seminal book called Creative Youth: How a School Environment Set Free the Creative Spirit, which argued that most students were innately poets and artists, but the American education system was designed to destroy their creative impulses and devalue their innate gifts. Rather than teach poetry, Mearns argued that it had to be nurtured in the young poet. “Poetry,” he wrote, “an outward expression of instinctive insight, must be summoned from the vasty deep of our mysterious selves. Therefore, it cannot be taught; it may only be permitted.”

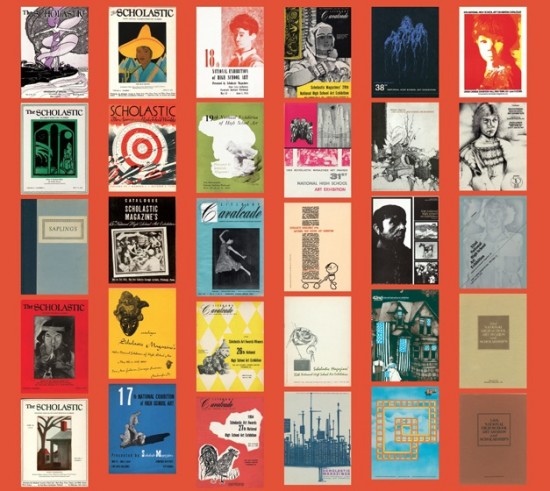

In the book, there is a beautiful spread of Scholastic catalogs featuring winning work beginning in the 1920s. How well do you think they snapshot each decade?

Yes, the spread of catalog covers does a beautiful job of conveying the progression of The Awards through the decades. In the covers, you can see an evolution of aesthetics that mirrors the history of 20th century art, but you also can sense the timelessness of the creative spirit. To be clear, I take no credit for the beauty of the book. Meg Callery, the graphic designer, did an incredible job, elegantly and thoughtfully bringing the ephemera and history to light. And Jeanette Anderson, in many ways the unsung hero of the publication, doggedly culled and organized the materials that were featured in the publication. They deserve all of the credit.

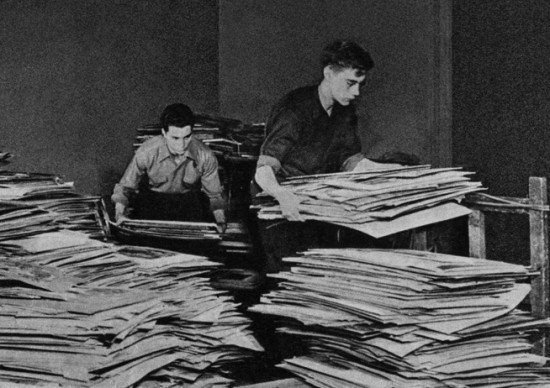

We heard that you used to collect Awards artifacts that you’d find while you worked at the Alliance several years ago, prior to the creation of our Archives. How satisfying was it to see our Archives come to life?

It’s been such a pleasure to see the archive finally come to fruition. One of my chief frustrations when working for the Alliance was never having enough time or resources to properly care for and preserve the rich history of The Awards. It felt like a crime to have all of these files full of ephemera stacked in boxes in my office, or shoved haphazardly into the back of a storage space. These assets should not only be archived, but they should be made accessible to future generations, so that young artists and writers will have a sense of community and solidarity with those who have come before them.

What were some of your favorite ephemera to find (i.e. letters, photos, news clippings, etc.) during the making of The Great Encouragement?

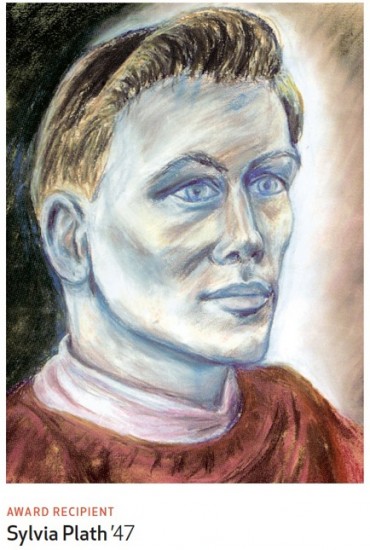

There were so many. I discovered a journal entry by Sylvia Plath in which she describes being notified by the school principal that she won a Scholastic Award. She was both sincerely moved by and slightly cheeky about the honor, in her already inimitable style. I found a newspaper clipping confirming that the filmmaker Ken Burns had won an honorable mention for an essay. Jeanette Anderson, my tireless editorial collaborator, tracked down Andy Warhol’s nephew and talked with him at length about The Awards. We learned that he was also an artist and had become an accomplished children’s book author. Jeanette went to the New York Public Library and pulled high school literary magazines featuring the nascent writing of the young Truman Capote. She also tracked down one of the core source texts we used for the early history, The First Forty Years of Scholastic Magazines, written by Maurice Robinson’s secretary, Thora Larsen, whom he describes in a footnote as “my strong right arm for twenty years.”

Tell us about the Hobby King and his impact on the Scholastic Awards.

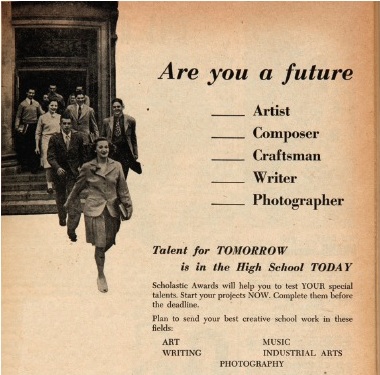

One of the most influential administrators of The Awards during the 1940s and 50s was a dapper, charismatic jack of all trades named Karl S. Bolander. In addition to running the Awards, and building the regional network that now administers the program locally, Bolander traveled the country delivering motivational speeches about the importance of hobbies. He was known as the “Hobby King,” and claimed to have cultivated 244 personal hobbies! The main argument of his lectures, which he delivered at conventions, and for school assemblies, luncheon clubs, and women’s clubs was that hobbies defined our moral character. How people spent their roughly 2,000 hours of leisure time each year, he asserted, would shape who they were and the course their lives would take. He was a powerful evangelist for “The Great Encouragement” of which Maurice Robinson wrote in 1928.

What surprised you the most about delving into the Archives?

One of the greatest surprises was just how closely The Awards were intertwined with the early history of Scholastic. At one point, in the late-1930s, the Awards staff comprised of roughly half of the company. There were 6 people running The Awards out of 15 running Scholastic. This high school art and writing contest that Maurice Robinson first founded to sell magazines, tapped into a need that was so great that it soon overwhelmed Scholastic and threatened to bankrupt the company. He and the company had stumbled upon something so powerful and important that they were willing to risk everything, putting their values before profits, in order to keep it alive. That we are now celebrating the 90th anniversary of The Awards is really a testament to the vision and sacrifice of the Scholastic staff during those first two decades.