Guest blog post by Haris Durrani, Editor, The Best Teen Writing of 2012

Last week, I ventured across the river to the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM). The National Book Foundation-funded series at BAMcafé, Eat, Drink, and Be Literary, welcomed Haitian-American writer Edwidge Danticat to read and talk about her work, and the series’ publicity team graciously invited me.

Ms. Danticat is not only a recipient of numerous writing awards, but a special friend of the Alliance. In 1997, she wrote a letter of encouragement to young writers now on display in our lobby at 557 Broadway —stop by to read it! This year, she served as a National Writing Juror for the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards. But what made my visit to Brooklyn more magical? Just a few weeks ago, Danticat generously agreed to write the Foreword for The Best Teen Writing of 2012, of which I am the Editor—and I couldn’t wait to meet her in person!

Dinner was served on the second floor of the Peter Jay Sharp Building. Afternoon light poured in from windows perched high on the tall ceilings as I chatted with other guests about books, libraries, and writers. Soon Danticat herself entered and sat at a nearby table. I seized the chance to greet her before the program began.

Generously, Ms. Danticat expressed her enthusiasm for Best Teen Writing, the annual anthology of stellar Scholastic Award-winning work. Like Danticat’s writing, so many of the works in this year’s edition will be about immigration, political oppression, and social justice—pressing issues in today’s age of social, political, and cultural flux— so I am especially delighted to be working with her.

Deborah Treisman, Fiction Editor for The New Yorker and moderator of the evening’s discussion, introduced the author. Danticat, a MacArthur Genius award recipient and multiple National Book Award Finalist, was raised by her aunt and uncle in Haiti until she was 12, when she emigrated to the U.S. and joined her parents in Brooklyn, NY.

“ ‘Writing is about bearing witness,’ ” Treisman said, quoting Danticat. “It’s also about a search for identity,” she added before inviting Danticat to the stage.

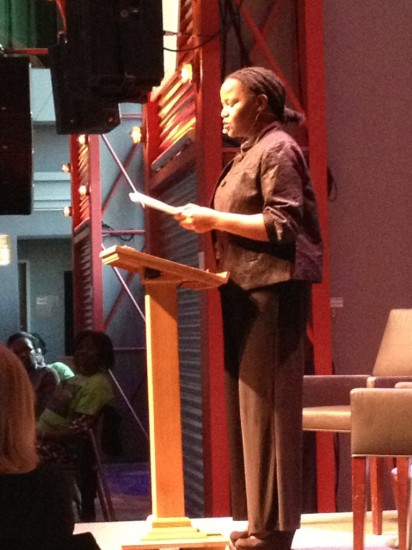

Danticat set up the piece she would be reading that night, titled “The Anniversary,” from a book that had been “kicking her around” for the past few years. She described it as a story about a “gossipy radio show in small town Haiti.” News gets around faster there on the radio, she explained, than in the newspapers, because of the call-ins and local gossip about the latest stories circulating in the community.

Once she began to read aloud, her words captured me. As in her previous work, her writing carries a passionate attention to character detail.

“The Anniversary” takes place in the same Haitian town as her National Book Award Finalist Krik? Krak! The protagonist’s husband is murdered—“Like most crimes in Haiti,” Danticat wrote, “her husband’s murder was never solved.”—and later the woman’s daughter is accidentally killed when a car crash sends her flying off her motorcycle. The story takes place on the 6th anniversary of her daughter’s passing as the woman struggles to overcome her grief.

Danticat’s writing often deals with both political and personal realms, and “The Anniversary” was no exception. The context of the husband’s murder hints at the social and political climate in which her characters live. At the same time, the protagonist’s suffering is described in the raw language of grief as the woman imagines how her daughter might have grown up.

After the reading, Danticat said that her family’s oral story-telling inspired her to start writing: it was a way to tell stories without the daunting presence of an audience. Still, it was hard to imagine herself as an author in part because so many of the authors she read in school in Haiti were “French and dead.” “It took me a while to realize I could be a writer,” she said.

When she first moved to America, she read through the small bookshelf of Haitian literature in the Brooklyn Public Library. “I read as a way to go home, to go back to Haiti,” she said, adding that some of these stories were by men and women who were killed by Haiti’s oppressive regime. “Locally,” she added, “being a writer meant being a kind of rebel.”

Treisman asked why she writes in English rather than her first languages of French and Creole. Danticat quoted the epigraph in the beginning of Junot Diaz’s Drown, a poem by Columbia Professor Gustavo Pérez Firmat:

The fact that I

am writing to you

in English

already falsifies what I

wanted to tell you.

My subject:

how to explain to you that I

don’t belong to English

though I belong nowhere else.

She explained that when she was learning English in the U.S., she was at “just the moment when starting to write was coming together.” In Haiti, French was taught in school and Creole was “more intimate,” spoken at home. But in the U.S., English became a “neutral” language in which to write. After all, she added, if she wrote in Creole her family might frequently grumble, point to a page, and say, “Ah, that’s not the right word.” At least, she joked, they trusted her English.

She enjoys “writing in layers” so that readers can re-read and catch aspects of a character they might have missed. Through her op-eds, she said, she can push directly for political and social change, but it’s through her fiction that she can explore multifaceted characters—often within the setting of political oppression—in order to illustrate the quirks and layers of human nature.

I found this particularly significant. During the 2012 National Awards Ceremony at Carnegie Hall, Scholastic Award alumna and Princeton astrophysicist Lucianne Walkowicz compared art to science, in that both are a way to discover fundamental truths.

In addition to being a conduit to truth, writing too can serve as powerful agent of social change. In some ways that is what this year’s Best Teen Writing is about. Danticat’s subject matter and style, grounding situations of political, social strife with the complexity of the human condition, echoes these teen writers’ voices and concerns. I feel so inspired and lucky to be working with her. What can I add? I look forward to her foreword!