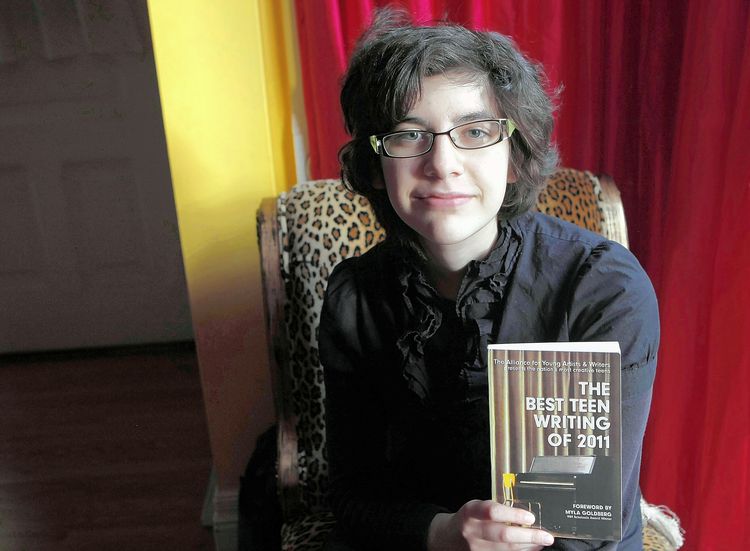

January’s Writing of the Month comes from Ava Tomasula y Garcia of South Bend, Indiana. Ava won a Gold Medal for Short Story in 2011. She can’t imagine not writing because she is fascinated and inspired by the ways that people communicate. Her winning piece, Terra Obscura, was featured in The Best Teen Writing of 2011, a student-edited anthology of prize-winning pieces from The Scholastic Writing Awards that expresses the thoughts and aspirations of our nation’s youth. Ava recently appeared in South Bend Tribune‘s InTheBend.com, where she talked about her work. Check out her short story after the jump!

Terra Obscura:

A land. A house. My house, my house; my father built it. We say.

We say, my mother, my brother, my wife. This is my daughter. My son. This life—mine—I bought it. Mine, mine—ownership.

But this house is not mine. This land.

Whose?

And so the story crumbles here, like an unkempt house, no longer a home—caving in on itself—falling in on its my ownself, leaving only chips and splinters to mourn silently in corners, erasing and so also hiding themselves from the, corrosion of constant ice form, ice melt. It is unimportant. It is cold, covered with ice and neglect.

“That house belongs to—” A catch in the throat. A tangle of loss.

Welcome.

So to think about the mine of the house, my (your) little son and father, you have to reconstruct the house yourself. But only part—don’t finish it. Make it mine (yours) only halfway. Then picture that catch of the throat, that intake of breath, that about to, that almost—cracking through the ice, and you will have them. Yours.

There is a photograph. A very famous photograph.

Yours?

His father—your father—was his hands.

Have you ever held a photo

of a house or person,

up to the same house or person,

now much older,

dilapidated,

almost melting?

Transposing the now in the photograph

to the now staring, cracked-windowed

and glassy-eyed, at you?

Everything he had came from his hands, but like everything, everything he lost was because of them.

He comes up through the ice with hands held open, in front and first.

The father had built the house, house through will alone although it’s still a home, with his hands. Ice blocks. He had tanned skins and picked grasses. He had held his son with the hands, had made dolls and slaughtered animals and bandaged cuts. He had spoken with the hands, translating his thoughts, and feelings of thoughts, into the outside world of rough and garbled words. He had even thought with the hands, had run them through his hair and let them finger what they might as he prayed silently to himself.

He had seen himself with them, seen himself in his son. The father had watched himself not himself; a him that has so little to be sorry for, when he stroked his (child’s) sleeping face.

Soft, child hands, unhardened and quiet with the certainty of ice form, not having seen ice melt.

His hands were young when he did these things, lived those little lives. Fine, unsullied by years of sun up, sun down. Ice form, ice melt.

But now he is old.

Your fingernails grow about

The same amount

As the continents

Move

Every year.

If he had lived here, today (not yours anymore, too complex), he might have known how many birthdays he had had (68), or how much his brain had shrunk since he was about 26 (roughly 8 percent), or even that he would be laughed at by people younger than his son, because he didn’t know what F-A-T-H-E-R spelled. Or that, years and years from his now, the ice shelf that held his home and son would break apart and melt away, helped along by those grown, laughing readers who don’t know and maybe shouldn’t know how to begin an apology.

A single snowstorm

Can drop 40 million tons

Of snow,

Carrying the energy equivalent

To 120

Atom

Bombs.

But he is in his now. He knows that he will live here on the sleeping shelf with his son and the caribou that breed there for many tomorrows.

The hands first held his son just before the caribou fawn began appearing as fawn pin pricks next to larger mother-tears on the shelf. Just before the exhausted bodies of new mothers began falling into the snow and freezing.

At that time, he taught his son how to use his own baby hands, how to keep them soft and young for now, because the father—his son’s—was there to bear the age for both of them, to hide the dead mothers and bury them in the snow at night before his son could see and be sad, before his son’s veins bulged under his soft hands’ skin as well. Instead, the father guided his son’s grasping hands in making tiny villages out of snow and ice, in drawing with burnt sticks, making patterns with wool and color and telling stories with the sons of their hands—shadows—becoming now a bird, now a man, flickering on the warm walls.

But this prehistory, this lineage of their lives, is not history worthy of making.

To the world, to the nows around them, not on the shelf, they are nothing, until a photographer that is famous in a now of cities, magazines, conferences and books comes to the shelf and captures their image.

They are a sub-story, or just storyless. Handless.

They are a family on their way to vanishing, an instant trapped in a photograph, a now that has since disappeared, or changed into disappearance, no longer there for the photographer to return to, if he ever did, which he did not. He had his prize.

As they are farthest away

From the heart,

Hands tend to become

Frostbitten quicker

Than any other

Part of the body.

Once, when the son had seen caribou young born on the shelf six times, he sat on top of his father’s shoulders and pointed at the pin pricks miles away on the flat shelf. He is laughing, at least, in the memorized image of the day he is laughing, clinging to his father’s neck and upheld hands, and the father is too, saying, “Not so tight, not so tight!”

Is it love to want to die there, inside that image? That photograph in the son’s memory, him, with his father, not knowing about mothers and buryings deep in the night?

Caribou

Can smell lichen

Up to three feet beneath

The snow.

The story is about animals.

Across the shelf, a caribou mother is walking with her son, already delirious and weak from (ice form), but she is still leading him (ice melt), growing more and more tired, until she lets slip that tiny life, and it falls, falls onto the already cracking shelf and stays there while the mother keeps walking until she too collapses like a something that falls all at once.

The father puts his own son down on the ice and snow, and runs ahead to the little life lying there near the already freezing mother, running and forgetting his son’s eyes and hands for a moment, for he is caught up in doing here what he does at night on the shelf bury mothers and kill already dying sons. He has to do what he does when he leaves his son to happily dream about sons and fathers and caribou inside their warm home.

He can tell there is nothing to be done, nothing hands can do for the little caribou son now, except hold it. And he does, he holds its head tightly and sings a very old song with his eyes closed while his human son sobs, standing there, on the shelf by his father, growing veins and wrinkles.

Then, the animal dies.

Camera comes from

Camera obscura,

Which means “dark chamber.”

The son would continue the story, continue his memory from there. He would think, if it were him lying there in the snow, if the last thing he saw was his animal mother falling down in the snow and the ice, and if it was the image of the father and his son that found him at the cracking edge of the shelf, maybe his leaving took a home with him forever. Like a photographed house that has since been demolished.

And since it was the son and the father who found the animal there on the cracked ice, maybe the difference between them melted away, hand gave way to hoof and hoof gave way to hand.

No matter. The son loves this story. This photograph. He loves this fatherless, handless, motherless, storyless story of a created time before the fawn son died, before the crack his father is sitting on gave way beneath him and his caribou son and they disappeared forever in the cold, shadowy water pulsing beneath the shelf.

It is a story he loves to death, and loved before the house and the shelf and the son melted into another now, a now that could, and had sons and daughters, they’re my son, my daughter, my mother, my father. A my now that cherished the photograph of the son and father, liked to think from warm museums and houses of them alone on the shelf, with howling winds and savage animals. Liked to think of them breaking through the ice, mangled hands first.